How to be Wise, Happy, Useful, and Rich

Self-help advice from a murder suspect with a backwards name; PLUS Extrasensory, Rocketbelt doc, and big tech takeover

In September 1847, a man with a backwards name gave a lecture titled “How to be Wise, Happy, Useful, and Rich” at the Literary and Mechanic’s Institution in Winlaton, an industrial village in the North East of England. The lecture, a seemingly prescient precursor to the modern trend of self-help books, podcasts, and YouTube videos, was received “in the most favourable terms”.

So, too, was the lecturer, an unusual fellow who billed himself as the author of a book that had never been published. He was a former travelling beggar who had been arrested for murder before reinventing himself as a self-help guru and “Professor of Moral Philosophy and Phrenology”. Although it was not entirely his real name, people called him George Egreog Droffnore.

It was during the mid-1830s that Droffnore first came to the public’s attention as a notable eccentric travelling across England, selling matches, repairing pots and pans, and undertaking manual labour. He was a large, scruffy man with a huge unshaven beard and long unkempt hair. But, newspapers noted, he was “no common vagrant”.

Giving his name at that time as Egreog Drofnah, he had, for reasons “presently concealed”, undertaken to travel across England in the character of a mendicant and vowed to raise £100 before he would shave his beard, cut his hair, sleep on any bed, drink any alcohol, smoke tobacco, or take snuff.

He set off from Penistone in Yorkshire in April 1836 and, by mid-1837, had travelled around 300 miles. But his uncut beard and hair made clear he had not yet earned his £100 — he claimed to have earned £60 and given it away in charity. Then, in the village of Weobley in Herefordshire, “Drofnah” was arrested for murder.

Drofnah was brought before magistrates and charged with killing John Haycocks in Bewdley Forest, near the village of Rock, around 30 miles away. Haycocks had been shot dead in an apparent case of mistaken identity. Police Constable Smith, who arrested Drofnah, said he had received a handbill offering a £100 reward and containing a description of the suspect, Thomas Watkins. Smith said a witness had told him that Watkins had travelled, disguised with a long beard, to Weobley. “Drofnah”, said Constable Smith, was Watkins.

Drofnah denied this, although he was hardly cooperative. He said the name he was travelling under was George Egreog Drofnah, and he refused to give any other. But he said that on the day of the murder, he had been working in Weobley as a joiner helping to build the Union Workhouse. He produced his handwritten journal to confirm this fact. Drofnah was remanded in custody until Constable Smith’s witness could be brought to court.

A few days later, the witness admitted he could not swear that Drofnah was Watkins, and added that he and Smith had agreed to share the reward. Two men who had worked with Drofnah on the Workhouse did positively swear that they knew both Drofnah and Watkins, and Drofnah was not the wanted man. Drofnah, described as “evidently a clever though extraordinary man”, was released. Constable Smith and his witness were reprimanded and fined. Watkins was formally charged with the murder, although records suggest he was never apprehended.

After that, Drofnah spent several months building a “French piano of his own making”. “Although totally ignorant of music,” said the Hereford Times, “he has, by perseverance, accomplished his purpose and is now attempting to complete the undertaking as a travelling musician.” The newspaper also noted that Drofnah intended to publish his journal. Drofnah (or “Drofnore”) placed an ad in the paper requesting subscribers for his book, which does not appear to have been published, although a lengthy extract — a treatise on the benefits of schools, reading societies, and mechanics’ institutions — was printed in the same paper.

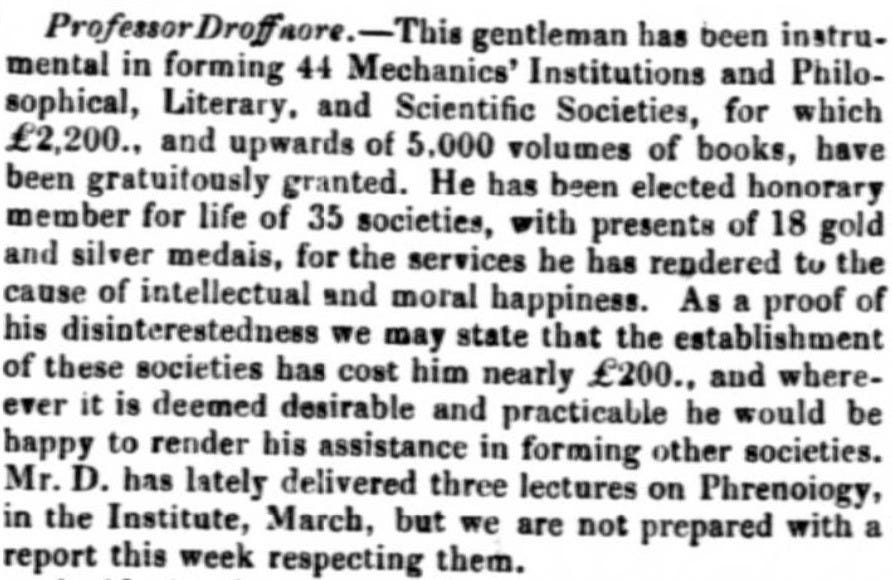

After that, Drofnah / Drofnore / Droffnore became associated with several fledgling mechanics’ institutions — aimed at providing education, particularly in technical subjects, to the working class. He gave lectures and chaired meetings across the country, and promoted the formation and expansion of similar institutions. But who was George Egreog Drofnah?

You don’t need to be a linguistics expert to work out that “Egreog” is “George” spelled backwards. And “Drofnah” is the reverse spelling of “Hanford”. His real name was George Hanford, and he was likely born in Leicestershire around 1791. He married Mary Pryor in 1814, and the couple had a daughter, Anne, in 1818. Whatever prompted his transformation into a travelling mendicant was never properly revealed. And, in 1847, as George Egreog Droffnore, he ended up in Winlaton.

The Winlaton Literary and Mechanics’ Institution had been formed in February 1847 by a group of young men including Joseph Cowen Jnr, the 18-year-old son of Sir Joseph Cowen, a former blacksmith’s apprentice who became a wealthy coal mine and brickworks owner. Cowen Jnr worked in his father’s businesses and shared his radical political ideology. Cowen Snr had protested the Peterloo Massacre and was a member of both the Winlaton Chartists, a working-class movement for political reform, and “Crowley’s Crew”, a group of working men associated with Ambrose Crowley’s Winlaton iron works.

Both the Winlaton Chartists and Crowley’s Crew were known to take up arms to protect their interests. During the 1830s, the chartists turned Winlaton into an armed fortress, blocking approaches with cannons and pikes, to defend themselves against government troops. As a result, Winlaton earned a reputation as a volatile and anarchic place. But the Literary and Mechanics’ Institution, alongside the associated Subscription Library, which held 900 books, aimed to change that reputation. It was formed “for the purpose of mutual improvement” and to show that Winlatoners “can talk as well as beat the anvil”. Unlike many other societies of the era, women were welcome to join as members.

“Some few years ago, Winlaton was notorious for the brutal ignorance of its inhabitants,” said the Darlington and Stockton Times. “The main of them were scarcely animals.” But, a few young men, “lamenting the condition of the district,” had formed the Institution with “astonishing” results. In particular, the Institution’s members had founded a Sanitary Association to tackle preventable causes of disease and death. “This little manufacturing village is an illustration of what two or three public-spirited individuals can do when they are inclined to pull together,” said the newspaper. They were determined to “make a long pull, a strong pull, and a pull together.”

Droffnore was described as “the author of a work on Man and Self-Culture, etc”. Like his journal, there is no record of this book being published. He must have liked Winlaton, as he stuck around for at least a few months. At a meeting of the Institution in November 1847, Droffnore acted as chairman. By this time, the Winlaton Institution was part of the Northern Reform Union political network. Joseph Cowen Jnr was the Union’s treasurer (and Droffnore was an honorary member). Cowen Jnr went on to establish the Newcastle Daily Chronicle newspaper and become a Liberal MP who eloquently campaigned for social reform.1

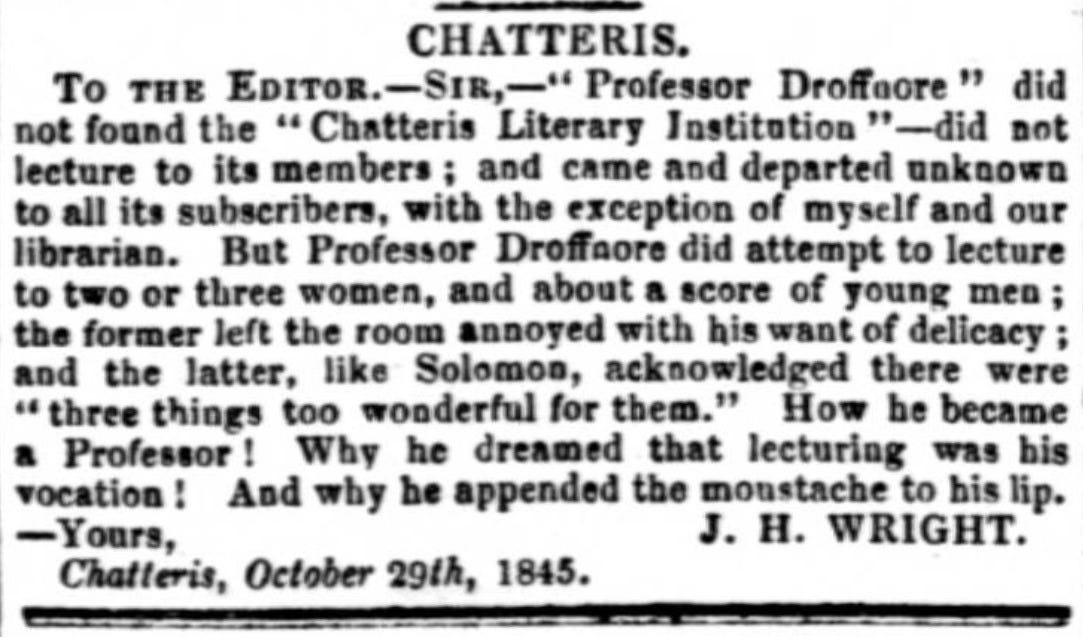

As for Droffnore, he continued to give lectures at Mechanics’ Institutions through to the 1850s. Although his lectures were not always well-received (his interest in the junk science of phrenology and his argument that humans could not hear and smell at the same time were particularly open to ridicule), Droffnore played an important role in the self-improvement of working-class communities across England. There are numerous reports from Tyneside to Devon of literary and mechanics’ institutions and other self-improvement societies being founded as a direct result of Droffnore’s visits and lectures.

Droffnore died in 1856, aged about 65, in poverty-stricken ill-health at the Madeley Union Workhouse in Shropshire. An inquest investigated whether the local authority’s relieving officer could be blamed for his death for sending him into the workhouse. But a jury found that the relieving officer had done everything he could for Droffnore, and gave a verdict of death by natural causes. The man with the backwards name would soon be forgotten, but he left quite a legacy and should perhaps be better remembered as an unusual and eccentric working-class hero.◆

This is the second of my posts about the weird world of Winlaton (“Win-lay-ton”) — a historic and mysterious village in the North East of England. You can find the first post here. Next month, we head into the woods on the hunt for the Winlaton Wild Man.

If you’re not already a subscriber, please sign up for free to receive new posts every month. And if you think you know someone who might like to read Singular Discoveries, please share this with them and encourage them to join us!

Recommended

Podcast: Extrasensory

In Hexham, North East England, in the 1950s, a milkman named John Pollock made a remarkable prediction. His two daughters, who had died in a tragic accident, would, he said, be reincarnated. Pollock was clearly a crank — even his wife thought so. Then she became pregnant and unexpectedly gave birth to twin girls. As they grew, the twins displayed remarkable similarities to their deceased sisters, and seemed to have memories of their sisters’ lives — and the terrible accident. Pollock claimed his twins were proof of life after death, and some scientists agreed. But was Pollock really a believer, or was he a fraud? Extrasensory is a spooky, atmospheric listen. It’s overly melodramatic in places, but it’s a fascinating story of a family bent by grief to believe the impossible — because reincarnation is impossible, right? You can listen wherever you get your podcasts (and wherever you get the Singular Discoveries podcast). ◆

Notebook

The Rocketbelt Caper lifts off

Last month, I wrote that 2025 would mark the 20th anniversary of the publication of the first edition of my book The Rocketbelt Caper. For most of those 20 years, the book has been in various stages of development as a movie or TV show. I’m pleased to say that it is now going into production as a documentary with an award-winning production company. More news to follow, but expect to see the documentary on your screens in 2026.

Big tech takeover

Like many people, I was alarmed to see the leaders of the big tech companies prominently seated on the podium at the US presidential inauguration. They had very publicly bought their seats alongside the new president on the understanding that he would loosen regulations, giving them free rein to become bigger, richer, and more powerful. Whichever side of the political divide you stand on, it’s surely worrying to think of the unelected likes of Google, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, and Meta running the world.

This year, I’m aiming to reduce my reliance on big tech and reduce the amount of personal information I hand over. It’s not easy. I stopped using X / Twitter. I very rarely use Facebook. I’ve switched away from Apple. I plan to shop less on Amazon. For me, Microsoft and Google are the really difficult ones to ditch. And, let’s face it, some of their stuff is really useful. I don’t want to stop using them altogether. There has to be a balance between privacy and convenience.

So I’m looking at restricting my usage and protecting as much of my privacy as the platforms allow. It’s not easy, but the first step is to go into the settings of your account on each tech platform and look for privacy settings. Then switch off everything you don’t want or need to hand over to Zuckerberg, Bezos, and co. It’s a small first step, but I think it makes sense to insulate yourself as much as possible as tech companies become ever more powerful.

What’s this got to do with Singular Discoveries? Well, I use multiple big tech platforms to make it. You probably use big tech to read it. As a writer, I’ve relied on evolving big tech throughout my career. (And I used to write about tech for a national newspaper.) So it’s a big deal for me, and probably for all of us. It’s something I’ll be thinking about over the next few months, and I’ll probably jot down some of my notes here or elsewhere as I attempt the impossible job of giving big tech the boot. ◆

Thanks for reading. More next month. Please help beat the big tech algorithms by subscribing and sharing!

In 1854, Joseph Cowen Jnr brought Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi to the Winlaton Institution. Garibaldi stayed with Cowen at his father’s home (Stella Hall, which was connected to Winlaton’s secret tunnels). Cowen had a statue of Garibaldi erected in the grounds of the home, although it was subsequently decapitated. A statue of Cowen Jnr was erected following his death in 1900 and still stands (complete with head) on Westgate Road in Newcastle.

Another extraordinary story from Winlaton. I read with pleasure. An excentric hobo who in the end turned insteumental to founding so many institutions. Please keep writing.

Ps. There is has been no sequel to the murder case? Has the murderer been eventually found? Wasn’t it strange that the two men who worked with Egreog also happened to have known the other suspect personally?

PS2. How do you find and create these amazing stories. Do you go to various archives to search about the same person? Some of those neespaper ads seem impossible to find. Are they digitalized so you can run filtered keyword search in the digital archive?