The Prince and the Secret Tunnel

A royal visit reveals a subterranean mystery in a strange ancient village; PLUS Killing Thatcher and 20 years of The Rocketbelt Caper

Edward, the Prince of Wales, was visibly distressed when he visited Tyneside in January 1929. In atrocious weather — heavy snow, freezing rain, and black skies — there were no crowds of flag-waving well-wishers as there had been for the visit of his father, George V, when the king opened the Tyne Bridge in the previous October. The prince was here to visit mining villages and survey the poverty that was plaguing the district. The weather only made things more drab and depressing. As one newspaper commented: “It was difficult to force optimism.”

Described as a “slight, boyish figure” dressed in two heavy overcoats and a woollen scarf, Prince Edward visited the Newcastle warehouse of the Appeals Fund — a food and clothing bank — and the Blaydon Employment Exchange. He heard desperate accounts of the effects of post-war mass unemployment and spoke to individuals who were attempting, against the odds, to help.

The prince faced “tragedy stark and naked” when he visited the village of Winlaton, once renowned for a prosperous ironworks but now relying on two failing pits. Winlaton sits high on a hill over the River Tyne, and the weather had made its steep approach inaccessible to the prince’s vehicles. According to the Sunderland Echo, “He had to leave his car and walk over the slag heaps deep in snow and up the hillside to the long rows of soul-destroying cottages.”

The scene he encountered was “poverty beyond description.” As news of the visit spread, people began to come out of their houses. “Women with white, bloodless faces stood at doors with their children, many of whom were barefooted and poorly clad,” said the Daily Record. “Men wore no overcoats. They had long been dispensed of to buy food.”

The prince visited the cottage of 74-year-old unemployed miner Frank McKay but found the blinds drawn and the place empty. A boy came forward and said McKay’s wife had died that night. “The old miner was so broken-hearted and distressed that he could not brace himself to meet the prince in his own home,” said the Echo. Edward went upstairs to the bedroom where Mrs McKay lay. A car was sent to find Frank McKay, and he did get to meet the prince. McKay said he would be selling the last of his furniture to pay for his wife’s funeral.

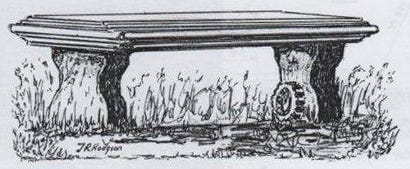

There was an interesting diversion when Prince Edward visited the house of former Northumberland Fusilier Taffy Lewis on Waterloo Street in the centre of Winlaton. The prince was told that under this house there was a centuries-old secret tunnel. The tunnel’s purpose had been lost to time, although there were many theories. Nearby, in the garden of Reverend Tebb’s chapel, stood an ancient stone table that had been removed from the tunnel. Whatever the tunnel had been built for, it was a passageway into Winlaton’s strange past.

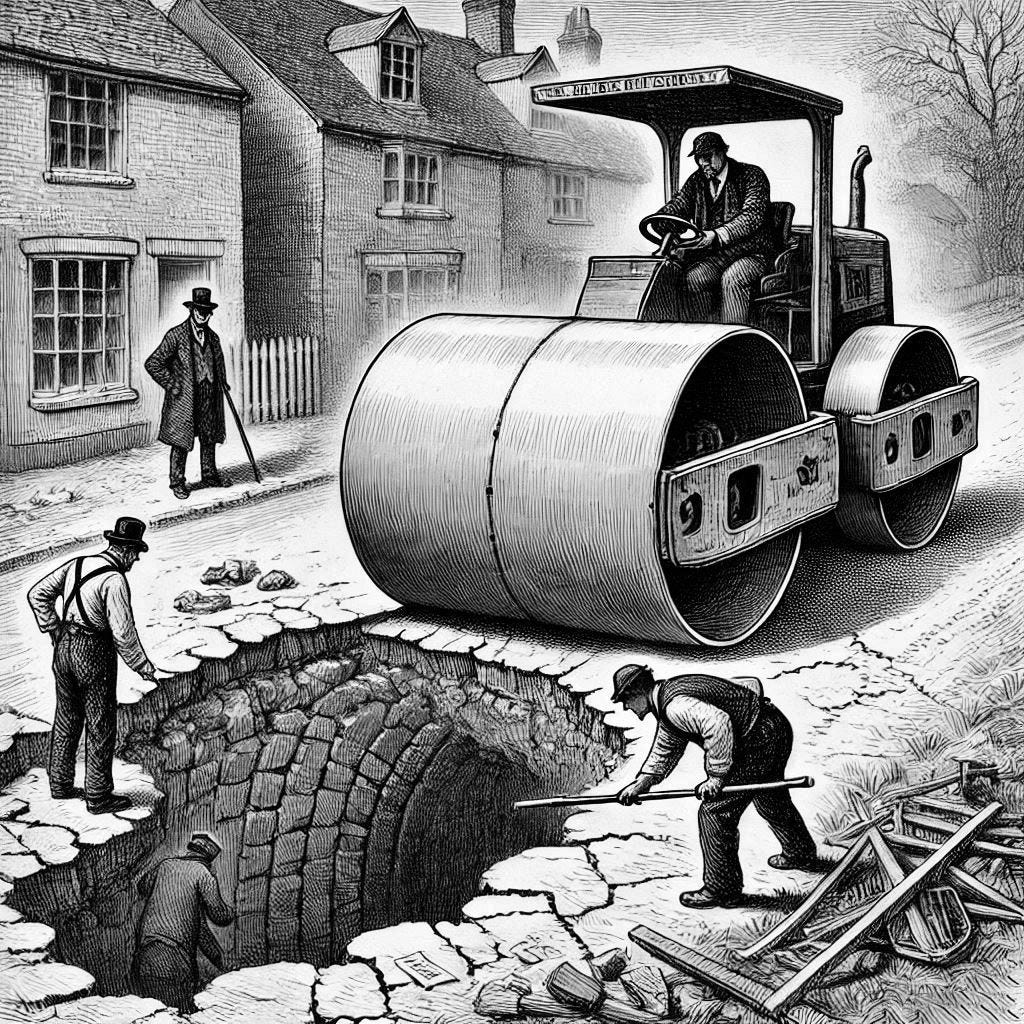

Eighteen months later, in September 1930, workmen from Blaydon Council were undertaking repairs in Winlaton when their steamroller broke through the road surface to reveal a cavity that turned out to be part of the underground tunnel, six feet deep and two feet wide and covered with eight-inch thick stone slabs. The tunnel, hewn out of rock, was identified as a long-fabled secret passageway between key locations in the village and down the hill to Stella Hall, about a mile away.

Unfortunately, further investigations of the tunnel were prevented by “the presence of foul air”. But further information was provided by Matthew Kirsop, a prominent Winlaton landowner and a member of the Newcastle Society of Antiquaries. The roadworks were connected to the demolition of a building owned by Mr Kirsop once known as Winlaton Hall or Winlaton Castle.

“We know that there is a subterranean passage from what used to be the old castle at Winlaton, afterwards known as Belt’s Buildings,” said Kirsop. “This passage leads across to Hallgarth Farm. Fifty years ago, one of the old stalwarts of Winlaton, whom I knew well, entered this passageway, which breaks off at right angles below Back Street and then runs to the Sandhill. He told me that he had walked underground as far as the Sandhill. Just below the Sandhill, he came across a large stone table. The passage then leads to the Low Town End, and no doubt the tunnel which has been discovered is a continuation and may lead to Stella Hall — its termination”.

There is a lot of local history to unpack here. Winlaton is an ancient village dating back to at least the Anglo-Saxon period from around the 5th century. Its history involves many wars, conquests, and rebellions. From clandestine monks to unruly earls and protesting chartists, the inhabitants have long been subject to persecution. Stella Hall, which was demolished in the 1950s, was known to have “priest holes” where the persecuted could be hidden from their pursuers. The leading theory was that a persecuted group — perhaps a religious order or rebel movement — built the secret tunnels to enable them to hide and pass unnoticed in the village.

While many towns and villages have legends of secret passages, Winlaton’s have verifiably been found. But they have never been fully explored. The entrance was sealed in 1930 and has subsequently been built over and never been knowingly reopened — which only deepens the mystery. The stone table stood in Tebb’s garden until the 1960s when it disappeared during the demolition of the old chapel.

As for Prince Edward, he became King Edward VIII upon his father’s death in January 1936 and reigned for just 326 days before abdicating to marry Wallis Simpson. If Edward was unlikely to have forgotten his visit to Winlaton, the detail of the secret tunnel had probably long since slipped his mind.

So why am I telling this relatively obscure story about a secret tunnel in an ancient village that few people have ever heard of? Partly because I grew up in Winlaton (pronounced “win-lay-ton”), and I know what a historic, mysterious, and downright weird place it is. I’ve written about Winlaton before, and that story, The Strange But True Story of the Witches’ Circle, is (surprisingly) one of the most-read things I’ve ever done.

Winlaton’s history is full of witches, ghosts, vampires, “wild men”, and other strange oddities. And the village is historically important as an early hotbed of industry and a stronghold of rebellion. Winlaton expanded to include Blaydon, home of the Blaydon Races, a famous horse race that spawned a famous song and its own colourful history. The song has become a beloved anthem of regional identity, and its (real) characters are archetypes of the people who lived and worked in Winlaton.

Perhaps most importantly, Winlaton is the birthplace of the English working class. It’s a much-overlooked oddity that I’m claiming as a fact. While the traditional narrative of the working class often starts with the Industrial Revolution, which began in England around 1760, Winlaton was a working-class community in the previous century. This is because an industrialist named Ambrose Crowley set up a major ironworks in Winlaton in 1691 and created a self-sufficient society for his workers, which raised them out of poverty and the restrictions of the feudal system, which had working people as serfs in thrall to landowners, lords, and the king.1

Crowley paid a decent wage and provided workers rights, including education and health benefits, subject to strict timekeeping and rules. The workers, “Crowley’s Crew”, were renowned for their skills with metal and their steadfast and resolute defence of their rights and freedoms in the face of government intimidation. There were many contradictions. The Crowley Ironworks made the railings for Buckingham House (the building that pre-dated Buckingham Palace),2 a literal symbol of the aristocracy constructed by ordinary working men. However, it also made chains for the slave trade, raising my ancestors out of poverty by helping to put enslaved peoples into subjugation.

Over the next few months, I’m going to write more about the weird world of Winlaton — alongside more typical diversions. Expect to read about, among other things: Selby the Vampire’s grave; Coffee Johnny and the hunt for the Winlaton “Wild Man”; Egroeg Drofnah, the eccentric tinker turned self-help guru; the Winlaton chartists and their armed battle for social justice; the ghost of the Unhappy Countess and numerous other spectres; the true story behind the Blaydon Races; and the real, forgotten story of the birth of the working class.

If you’re not already a subscriber, please sign up for free to receive new posts every month. And if you think you know someone who might like to read about very singular discoveries in a weird ancient village, please share this with them and encourage them to join us! ◆

Recommended

Book: Killing Thatcher by Rory Carroll

In October 1984, the IRA was looking to top its campaign of scattershot bombings and hunger strikes with a veritable “spectacular”. The aim was to blow up Brighton’s Grand Hotel during a Tory party conference and kill the Prime Minister. The bomber was veteran IRA volunteer Patrick Magee. The bomb exploded, but the plot failed. Five people were killed and more than 30 were seriously injured, but Margaret Thatcher escaped unharmed. “Today we were unlucky,” said an IRA statement, “but remember we have only to be lucky once. You will have to be lucky always.” Rory Carroll’s book is a forensic thriller, gripping despite knowledge of the ending. Although the plot failed, it came extraordinarily close to success and stands as a historic near-miss on par with Guy Fawkes’s Gunpowder Plot.

I’ve added Killing Thatcher to the Singular Discoveries bookshelf.*

News

20 years of The Rocketbelt Caper

2025 sees the 20th anniversary of the publication of my book The Rocketbelt Caper. It wasn’t the first book I wrote, but it feels like it was. It’s certainly the one with the longest and most interesting life. The first edition was published in 2005 with a rather dull cover featuring a lightbulb. Second and third editions were published in 2007 and 2009. The latest edition is available on Amazon. It’s the true story of three men who set out to build a James Bond-style flying backpack and became involved in a brutal feud. The least amazing thing about the story is that they actually succeeded in building the rocketbelt and were flying around with it. Then things went very bad…

This is the cover blurb:

"We finished the rocketbelt, and from then on there was murder, kidnapping, and all kinds of other stuff." - Brad Barker

When three men set out on a quest to build a real-life Buck Rogers-style flying machine, their obsession with the Rocketbelt 2000, or "Pretty Bird", shattered their friendship and set in motion an astonishing chain of events involving theft, deception, assault, a bizarre kidnapping, a ten million dollar lawsuit and a horrifically brutal murder. This book also reveals the secret history of the flying jetpack, involving Nazi scientists, James Bond, and the US Army. From sci-fi to reality, this is the incredible true story of the amazing rocketbelt.

And these are some of the reviews:

‘A delight to read. Genuinely stranger than fiction. Recommended.’ – Popular Science UK

‘The story has all the markings of a Hollywood blockbuster, and is a bizarrely unforgettable read.’ – The Crack

‘A can’t-put-it-down murder mystery that shows how obsession and betrayal can lead people to commit dastardly deeds.’ – General Aviation News

‘Reads like good movie material.’ – BBC Focus

‘There’s probably a Tarantino movie in this somewhere.’ – Fortean Times

If you haven’t read it, where’ve you been?! It’s been out for 20 years! You can find it on Amazon and on the Singular Discoveries bookshelf.*

Over the next few months, I might dip into my notebooks to reveal some behind-the-scenes stuff and updates from the last two decades. Expect tales of death threats, Hollywood adventures, and a cabin in the woods. Until then, you can read more on my website.

Thanks for reading. More next month. Please share and subscribe.

My definition of “working class” has little to do with any lack of wealth, skills, or education. It simply means those who work for a wage in order to live (or those who rely on someone who does). Those who work for a wage but have a financial safety net are generally middle class, and those who don’t need to work to live are upper class. Definitions of the working class as “low paid, with limited skills or education” are surprisingly widespread, demeaning, and quite offensive!

Correction added 17/01/25, “the railings for Buckingham Palace” replaced with “the railings for Buckingham House (the building that pre-dated Buckingham Palace)”, with thanks to Val Scully.

Main sources: Sunderland Echo, 29 Jan 1929; Shields Daily News, 5 Sept 1930; A History of Blaydon by Winlaton and District Local History Society, 1975; The Winlaton Story by R Anderson, from The Bellman, 1972 (https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/DUR/Winlaton/W7); Meldred: First Lord of Winlaton Manor by TR Hodgson.

*This publication features Amazon affiliate links. If you use them, I may receive a few pennies to help fund the newsletter. See our Amazon bookshelf here.

Your stories are amazing and quite unique! And what about the images, where do they come from? They fit really well.

Another great historical story Paul.

Keep the stories flowing!