The Plot to Blow Up the Tyne Bridge

How the north-east icon survived wartime peril: PLUS new book out *today*

Hi, welcome to a special edition of Singular Discoveries to coincide with today’s release of my new book, The Tyne Bridge: Icon of North-East England. To give you a taste, this is a version of a story that appears in the book. If you’re in the North-East, you’ll already be aware of the importance of the Tyne Bridge. If you’re not, welcome to the club!

In November 1939, a couple of months after the start of the Second World War, a Newcastle office clerk named George Duke was arrested for taking a photograph of the Tyne Bridge. “Apparently, some people do not know they cannot take photographs of bridges,” remarked an annoyed police inspector. Duke, who was 57 and from Elswick, told the police court he knew military objectives could not be photographed, but he thought this meant “soldiers’ guns and camps”. He didn’t think he was doing anything wrong, as picture postcards of the bridge were being sold across Tyneside. But he now realised he had been indiscreet and had perhaps jeopardised the safety of the bridge — and damaged the war effort. The court fined him £5 plus costs.

The Tyne Bridge, which opened in 1928, is one of Britain’s most iconic structures and has established itself as much more than a picture postcard attraction. Linking Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead in the North-East of England, the bridge has become a symbol of Tyneside, an emblem of the region’s cultural identity, and a monument to the Tyne’s industrial past. Following its grand opening by King George V, which was captured in an early globally-popular “talkie” movie, the bridge’s unique crescent arch design became recognised around the world.1

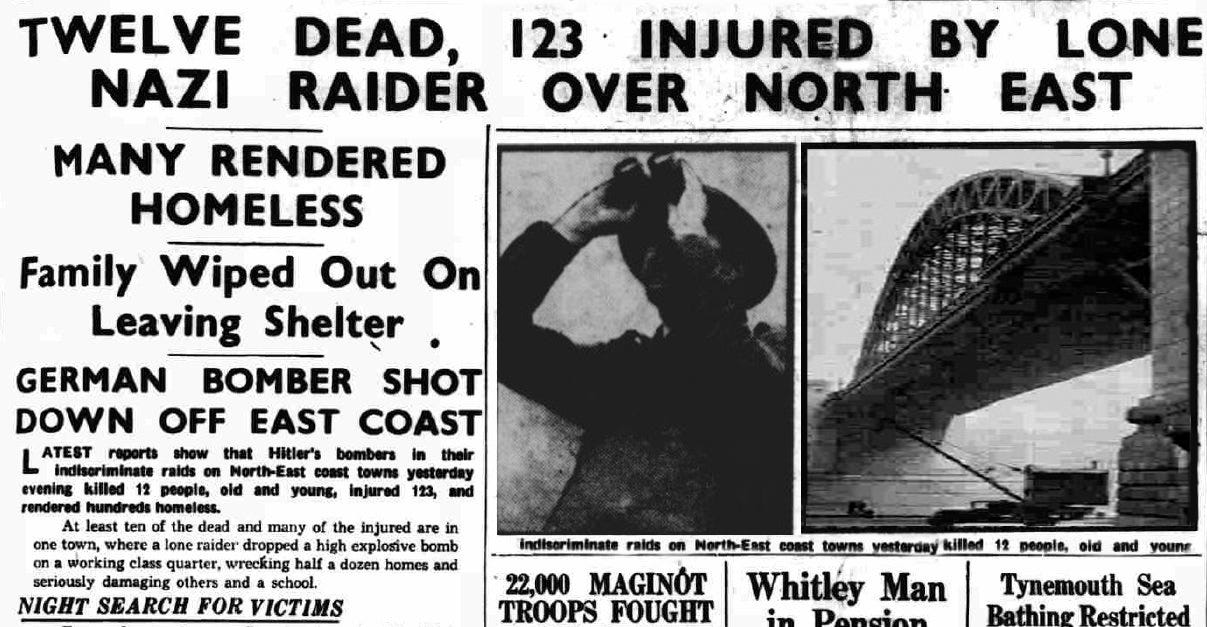

During the war, it was a conspicuous visual reference—and a prize target—for Nazi bombers. The first deadly raid came in broad daylight, at 5.30 pm on 2 July 1940, when a small party of bombers flew in from the North Sea and up the Tyne towards Newcastle. A Royal Observer Corps spotter at the D2 lookout post at Kenton followed one of the raiders through binoculars. “Plane approaching from East,” reported the spotter. “Steep dive… pulled out… Dornier 17… two explosions heard… columns of debris clearly seen… sirens heard… anti-aircraft fire.”2

The bomber’s payload narrowly missed the Tyne Bridge and sailed over the adjacent Swing Bridge and High Level Bridge. One of the bombs hit Spiller’s Old Flour Mill on Newcastle’s quayside. Thirteen people were killed in the raid, including several children, and 123 were injured. Tyneside’s newspapers, restricted from publishing information that might be useful to the enemy, reported only that “a high explosive bomb fell on the poorer quarter of a North-East town” and damage “seems to have been confined to a disused flour mill, latterly occupied by an extra warehouse by a local transport firm”. Warehouse workers had just left the old mill when the bomb dropped. One told a reporter, “I was lucky to get out in time”.

In August 1940, a fleet of as many as 300 Nazi bombers crossed the North Sea on the way to attack Tyneside. The Royal Air Force shot down up to 75 of the raiders, but the remainder dropped hundreds of bombs on Tyneside and Wearside. According to one story, an off-course Luftwaffe bomber that was supposed to target the Tyne Bridge accidentally flew ten miles upriver and tried to blow up the Wylam Railway Bridge. The bomber missed the bridge and dropped its payload harmlessly in the surrounding fields.

One night in September 1941, a few days after a particularly devastating raid and with blackout regulations in force, the electric lights on the Tyne Bridge suddenly began to blaze, illuminating the potential target for all to see. A steeplejack quickly scaled the bridge and extinguished one light but was called down by police before he could move on to the others. Eventually, after half an hour of perilous illumination, council officials switched off the lights and plunged the bridge back into darkness. The cause of the inadvertent illumination was never revealed.

On top of the threat of bombing raids, there were fears of an invasion along England’s North-East coast. Vital structures were primed for deliberate demolition to slow the Nazi advance. One of those structures was the Tyne Bridge, and the man with his finger on the detonation button was known as Andrew Clayton. Speaking long after the war, Clayton (a military and security advisor who declined to give his real name) revealed British Intelligence expected the Nazis to land on the Northumberland coast and proceed south through Newcastle. The assault on Newcastle would be assisted by paratroopers who would be dropped onto the Town Moor (and by German spies who were holed up in houses near the RAF operations bunker at Kenton). “The bridges across the Tyne would have been so vital,” recalled Clayton. “Had they been able to cross the river, they would have advanced without interruption.”

When the invasion started, Clayton would receive a telephone call containing a code word: “Humbug.” This was the signal for him to blow up the Tyne Bridge—plus the other bridges and the Newcastle Central railway station. He could have been forgiven if he felt something of a shiver run down his spine at two o’clock one morning in 1940 when his phone rang, and a voice on the other end said, “Humbug to you. I repeat: Humbug to you.”

Clayton hurried to his assembly point, along with around a thousand other men with different roles to help repel the invaders. But, before Clayton began his deadly mission, he was advised to stand down. This Operation Humbug had been a false alarm, “a little test dreamed up by Churchill to make sure everyone was on their toes”. But the plan to blow up the Tyne Bridge was genuine. “Happily, in the end, there was no destruction,” said Clayton. “However, we were more than ready.”

The Tyne Bridge was not destroyed by Nazi raiders nor by British defenders. More deadly bombing raids on Tyneside—around 31 in total between 1940 and 1943—killed and injured scores of men, women and children and destroyed hundreds of homes and other buildings. “And throughout all of this, the Tyne Bridge stood firm,” the Newcastle Chronicle later reflected, “a symbol of the determination of the people of Tyneside to withstand all that the Nazis could throw at them.”◆

The Tyne Bridge book — OUT NOW

It’s finally here. My new book The Tyne Bridge: An Icon of North-East England is out and available from all good bookshops today. Get more info and buy it here.

The book is a celebration of one of Britain’s best-loved structures as it approaches its 100th birthday. It’s packed with stories like the one above, plus loads of photos — some old, some new, and some specially restored for the book. It uncovers the forgotten histories of the Tyne Bridge's predecessors, tells the untold stories of the people who designed and built the bridge, and discovers how it became such a famous symbol of Tyneside.

It’s all packaged in a very handsome hardback that would make a lovely gift for yourself or a friend or relative. Feel free to buy multiple copies for everyone you know. (Christmas is only seven weeks away…) But don’t listen to me; listen to these fine folks:

“The Tyne Bridge, symbol of home and identity, is my favourite structure in the whole world and this book tells its tale-and that of its remarkable predecessors-with a rich plethora of wonderful stories. A very entertaining read.” — Michael Chaplin, playwright, former producer and executive at ITV and the BBC, and author of Newcastle United Stole My Heart: Sixty Years in Black and White

“Paul Brown's focus on the intimate human stories sets this work apart from the rest. While you should expect an insightful and comprehensive history of the bridges themselves, you will be delighted with the effort taken to shine a light on the touching stories that make the Tyne Bridge so magnificent.” — Kieran Carter, founder of the North East Heritage Library

“A magnificent feat of engineering, linking Newcastle and Gateshead across the Tyne, Paul Brown's biography of our great bridge is a testament to the drive, resilience and engineering ingenuity of the people of the North East.” — Chi Onwurah, MP for Newcastle upon Tyne Central

“The Tyne Bridge merited a book which Geordies can be proud of. Paul Brown nailed it with diligent research and expert storytelling.” — Andrew Hankinson, author of Don't Applaud. Either Laugh or Don't (At the Comedy Cellar) and You Could Do Something Amazing with Your Life [You are Raoul Moat]

“A Big River needs a big bridge and a brilliant book. A comprehensive and heartfelt tribute to the Geordie Golden Gate.” — Biffa, NUFC.com

I’ll be talking about the Tyne Bridge at the Books on Tyne Newcastle Book Festival at Newcastle City Library at 4pm on Tuesday 22 November. Get free tickets here.

In the run-up to the book’s release I’ve been posting illustrated threads about the Tyne Bridge’s predecessors on Twitter:

In case you missed it, there was another story about the Tyne Bridge in a previous edition of this newsletter:

That’s all for now. Please do share this post with anyone you think might enjoy either the Singular Discoveries newsletter or the Tyne Bridge book. Thanks for reading.

Sources: Shields Daily News, 14 November 1939, Newcastle Chronicle, 23 May 1945, Newcastle Journal, 3 July 1940, Shields Daily News, 27 September 1941, Newcastle Chronicle, 9 September 1991, Newcastle Chronicle, 12 July 1993.

Although the Tyne Bridge and the Sydney Harbour Bridge were built by the same contractor and designed by the same engineer and share similar features, neither is a copy of the other. The Tyne has a crescent arch and the Sydney has a spandrel arch. They were built concurrently, and the smaller Tyne Bridge was the first to be completed.

The Dornier Do 17 was a twin-engine bomber.