The Flying Man (and Flying Donkey)

Daredevil showman makes ass of himself; PLUS Jonathan Rendall, Lost Watch, Air Con

In December 1733, the Newcastle Courant carried this brief but remarkable tale of a showman known as The Flying Man:

“Newcastle upon Tyne, Dec 14. This Day se’night [seven nights ago], the Flying Man flew from the Top of the Castle into Bailey-Gate [1], and after that he made an Ass fly down, by which several Accidents happen’d thro’ the Carelessness of People not getting out of the way, tho’ a very great and timely warning was given; for the Weights ty’d to the Ass’s Legs knock’d down several, bruis’d others in a violent manner, and killed a Girl on the Spot.”

The Flying Man was a showman who toured the country performing a death-defying “rope sliding” act. He would rig a rope from a castle battlement or church steeple and perform a variety of acrobatics while warming up the crowds, which often numbered in the thousands. Then he would climb the rope and, wearing a grooved wooden breastplate, “fly” down it—while firing pistols and beating a drum or blowing a trumpet—with a jet of smoke streaming behind him. A companion would circle the crowd collecting donations in a hat, and the Flying Man would move on to his next venue.

Britain’s most famous Flying Man was Robert Cadman (or Kidman), known as “the famed Icarus of the Rope”. Likely born in Shropshire around 1712, Cadman sought permission to fly from tall buildings by offering to repair steeples and weathercocks while he was aloft. The Newcastle Flying Man might have been Cadman, although he had several imitators. Cadman was active from at least 1733 until February 1740, when he was killed during a performance at St Mary’s Chuch in Shrewsbury. His rope snapped, and he fell to his death in front of thousands of onlookers.

Thomas Pelling was another famous Flying Man, but he could not have performed at Newcastle in December 1733 because he was killed in the previous April. Pelling, from Lincolnshire, died when he hit the tower of the parish church at Pocklington, near York, after attempting to fly from its steeple. He was buried where he died, and a public subscription paid for a stone monument on the church wall. (In more recent years, Pocklington has celebrated Pelling with a replacement monument and a Flying Man Festival.)

Another “fam’d Flying Man” (possibly Cadman) flew from Edinburgh Castle into the Grass Market in May 1733, a few months before the Newcastle Castle performance. The Edinburgh Flying Man became fatigued while performing his tricks on the rope and begged the Castle’s provisioner to bring him a bottle of ale. But the “hard-hearted fellow” refused, and the Flying Man had to complete his performance with a dry throat.

Back in Newcastle, there are few further details about the Flying Man and his Flying Ass, nor the poor girl who was killed on the spot. The story was repeated in other newspapers around the country, and then in various historical tomes in subsequent centuries, but was never expanded upon.

There are further tales of Flying Men wrecking church steeples, breaking their necks, and having both legs amputated following terrible accidents. The death of Cadman in 1740 seems to have killed off the brief era of the Flying Man. William Hogarth did sketch one such performer in his lively 1733/34 engraving Southwark Fair, which shows—toward the top right—a man “flying” down a rope from a church bell tower. Possibly this was Cadman, his short-lived fame captured by the artist for posterity.⬧

Recommended:

Book: This Bloody Mary (Is The Last Thing I Own) by Jonathan Rendall (1997)

I’m occasionally asked to pick my favourite sports book—and this is it. Rendall is a down-on-his-luck boxing manager existing in the shadows of a fading sport and reflecting on how he got there. It’s a bittersweet love letter to the sport, a funny/sad/chaotic personal account, a British take on Hunter S Thompson, and one of my favourite books. Don’t just take my word for it. Tom Wolfe described it as “brilliant” and Tom Stoppard said it was “wonderful”. Get it here*.

You should also read Rendall’s Twelve Grand*, in which his publisher asks him to gamble a £12,000 advance and write about it. Things do not go well. There was a follow-up Channel 4 TV show, The Gambler, which is an extraordinary watch, and available to stream on All 4. He wrote about boxing, gambling, and drinking in columns for various newspapers, and very honestly chronicled his turbulent life. Tragically, Rendall died in 2013 aged 48. His Guardian obituary by Kevin Mitchell is very touching: Troubled writer Jonathan Rendall fails to elude his final deadline.

Article: The Watch that Came in from the Cold by Cole Pennington (Hondinkee Magazine)

An interesting tale nicely told about a battered Rolex Oyster watch that once belonged to a covert CIA agent. Read it on the Hodinkee website.

Article: Before Air Conditioning by Arthur Miller (The New Yorker, 1988)

Having recently returned from a very humid New York, I was interested to read this by Arthur Miller from the New Yorker archive. You can read it on the New Yorker website.⬧

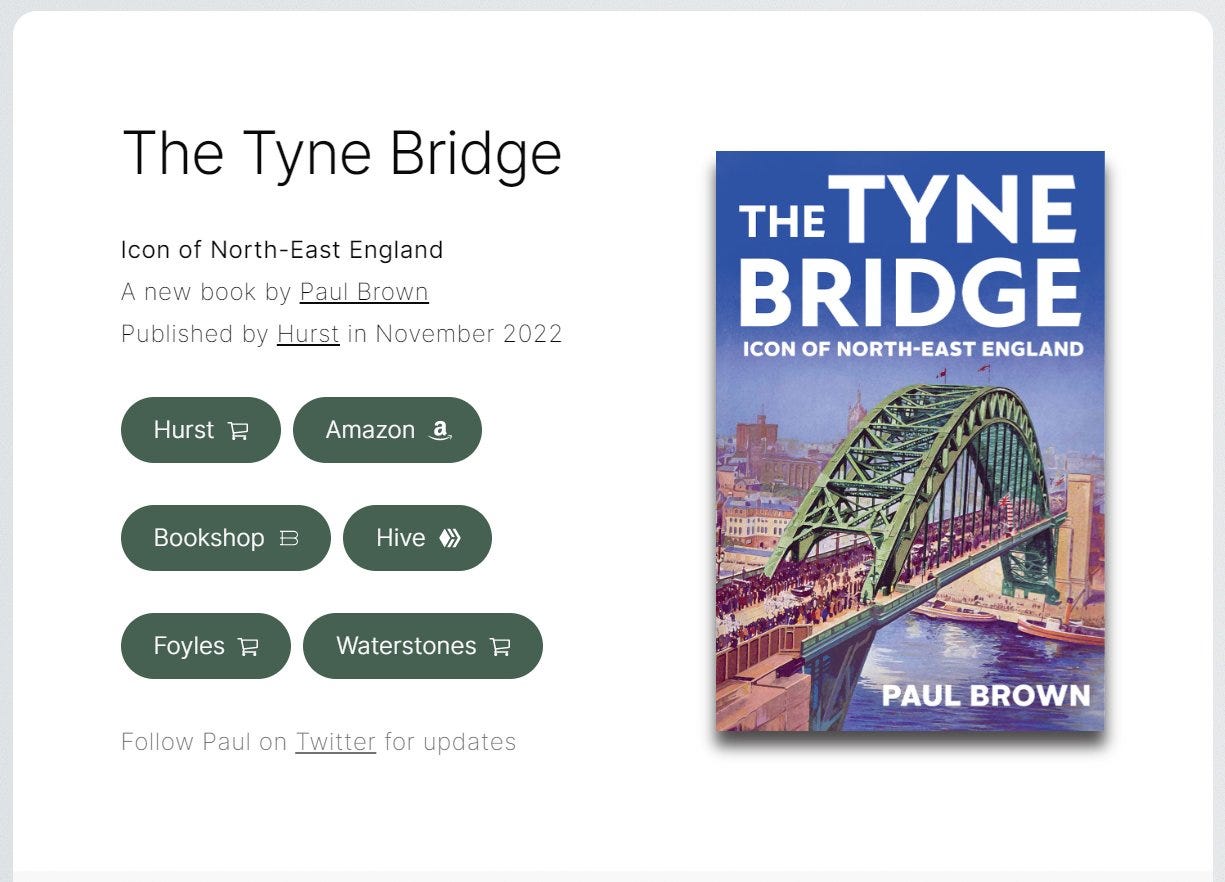

My book about the Tyne Bridge will be published in November. It now has a website here. Thankfully, funding has now been allocated to allow the Tyne Bridge to be refurbished, so it will still be standing when the book comes out.

Meanwhile, over on Twitter: We went to Blaydon Races…

Thanks for reading, subscribing and sharing. This newsletter will self-destruct unless you click this button:

[1] The Bailey Gate was perhaps the original entrance to the medieval “New Castle”, near the south-west corner of the surviving Castle Keep.

Main source: Newcastle Courant, 15 December 1733.

Ads: Links marked with an asterisk (*) are affiliate links. If you use them, we may receive a small payment to help with the running of this free newsletter.