The Cedar Box

The Vanishing Bank Manager part 3; PLUS Troubles on TV, and Hollywood's most bankable writer

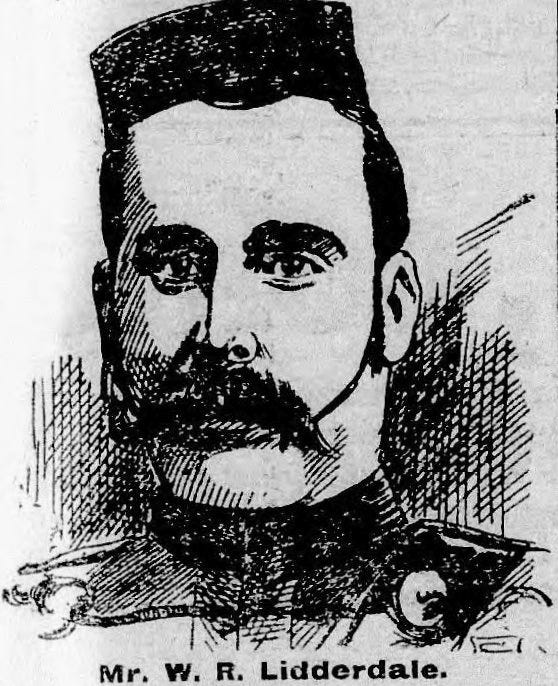

In the previous edition of Singular Discoveries, we continued the story of William Lidderdale, the vanishing bank manager, who disappeared a few days before his wedding to Bessie Chapman in 1892. Lidderdale’s disappearance was linked to a mysterious woman known as Miss Vining, and her yacht, the Foresight. Bessie attempted to have William declared dead, but after decades of investigations, the case remained unsolved.

Towards the end of 1945, several months after the end of the Second World War, a reporter from the Daily Mail went to Ilminster, Somerset, to meet a woman who had made headlines more than 50 years earlier. He found a “little old lady” aged about 77. “Yes, I am Miss Elizabeth Chapman… still,” confirmed the lady. “I remember Mr Lidderdale well. That name revives very tender memories.”

Elizabeth “Bessie” Chapman was the bride-to-be who was left behind when her fiancé William Robert Lidderdale vanished days before their wedding in 1892. Lidderdale, a respected bank manager, travelled from Ilminster to London to meet a client and never returned. He had sent Bessie a letter from London mentioning meeting a mysterious Miss Vining. Several days later, an obituary appeared in the London newspapers stating that William had died on Miss Vining’s yacht, the Foresight. Decades of investigations had failed to solve the mystery. Now, the reporter told Bessie, 53 years after William’s disappearance, a new clue had emerged.

It was found in a cellar in Hythe, Kent — about 20 miles from Margate and Westgate-on-Sea, where William was known to visit, and where Miss Vining’s yacht had been spotted by a coastguard. It was a battered box full of pieces of cedar. A furniture company found it during a clear-out and sold it for £5. The buyer assembled the pieces and found they made an “oriental” box “covered with carvings of Burmese characters”. Of particular interest was the fact that each piece of cedar was marked on the back with the words: “WR Lidderdale, 1896.”

If this was the same William Robertson Lidderdale who had disappeared in 1892, the cedar box had been marked four years after his supposed death. The fact that it had been taken to pieces and that each piece bore Willie’s name,” noted one newspaper, “suggests that this had been done to facilitate transporting it over a long distance and that Willie wanted to identify each piece for reassembly on arrival.” Had William faked his death and travelled abroad?

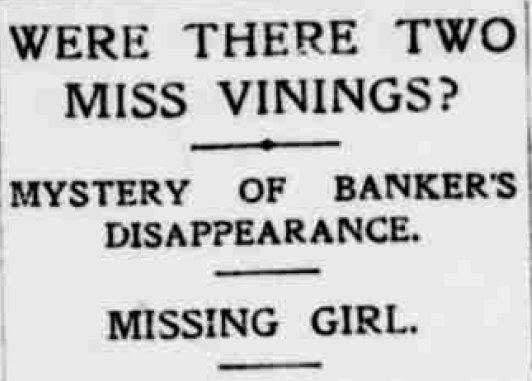

Interest in the case, “one of Britain’s biggest mysteries… which has baffled detectives and the whole of the legal profession for more than 50 years”, was rekindled. All these years later, the key to the mystery remained the identity of Miss Vining. A deep dive back into the archives reveals that the press did identify a Miss Vining who might have been connected to William Lidderdale. In fact, they identified four Miss Vinings.

The first was Julia Vining of Shepton Mallet. The census of 1891, conducted a few months before William’s disappearance, lists only one Julia Vining in Shepton Mallet. She is 43 years old — three years older than William — and is recorded as married, although she does not live with a husband. She works in a silk factory and has a 19-year-old daughter named Florence. Newspapers quickly ruled out this lead. “The scent was entirely a false one,” said the Shepton Mallet Journal.

The second was Julia Vining of Westcombe, a tiny farming community in Batcombe, about six miles from Shepton Mallet. This Julia Vining was born in 1865, meaning she was around 26 when William disappeared. She appears on earlier census records but not the census of 1891. She lived in a tiny cottage belonging to her father, a widower and farm labourer. She appears to have worked as a household servant. Most interestingly, newspapers reported the Westcombe Miss Vining had disappeared around the same time as William.

A Daily Express reporter attempted to track her down in 1907. “The missing girl is still remembered in Westcombe as exceptionally good-looking,” wrote the reporter. “She and her sister educated themselves by reading and associating with people in a superior social station to their own.”

Julia tired of the quiet village and moved to the relatively busier Shepton Mallet, where she lived “close to the lodgings of Mr Lidderdale, who was then engaged as a clerk at Stuckey’s Bank in the centre of the town.” She was said to make “constant excursions” to the nearby town of Bath. Coincidentally, William had told Bessie he had met Miss Vining in Bath.

According to the reporter, Julia disappeared “as suddenly and mysteriously as Mr Lidderdale did about the same time.” A friend in Shepton Mallet, Mrs Salter, called for her one day and found she had left. No one at her lodgings knew where she had gone. Mrs Salter remembered Julia as “Jul” or “Jewel”. “She was really a very pretty girl,” she said, “and I have heard her called “‘The Belle of Shepton’”.

“She never mentioned the name of Lidderdale to me,” said Mrs Salter, “but I was told that someone who was at the bank then was paying her a little attention.”

Back in Westcombe, Julia’s father had died, and there was no remaining family. But a former neighbour did remember her.

“I understand the girl went to London and made a rich marriage,” said the neighbour. “She was a sweetly pretty girl. As I remember, she had beautiful golden hair curling all over her head and the rosiest cheeks. Julia was well-educated for a village girl, and carried herself well in any company. We all thought she would do well in the world, and we heard that she had done so.”

Another neighbour, Mrs Wiltshire, said she had known Julia since she was a baby. “Can you give me any news of her?” she asked the reporter. “Is she alive or dead?” Mrs Wiltshire said she had not seen or heard of Julia since about 1892. “She was a handsome, ladylike girl. She had many friends here, but no one has any idea where she has gone.” The neighbour also recalled the last time she saw her. “She was dressed in a smart tailor-made costume and had a large travelling bag with her. I noticed that she was in an unsettled frame of mind, as though she was contemplating taking some important step… I judged that she proposed to leave the district and to accept some offer of marriage. I have never seen her since. I wish I knew what has become of her.”

The other two Miss Vinings identified by the press were even harder to locate. The third was “dark and particularly attractive” and “most probably never knew Mr Lidderdale”. And the fourth was a Miss Vining who had visited a friend at a house near William’s lodgings. “She appears to have answered with some accuracy to the description of the mysterious Miss Vining,” said the Western Mail, “both in personal appearance and social standing.” The friend had died, and this Miss Vining had never returned. But, the Western Mail concluded, “it is considered most probable that this was the lady whose name was in 1892 coupled with the disappearance of Mr Lidderale.”

The Western Mail also turned up another witness, “a lady who copied some letters for Mr Lidderdale”. She was convinced that William had gone to Margate to meet a real individual called Miss Vining. She was also inclined to believe he was dead, “possibly from foul play”, because in one of the copied letters, “the writer said that if she did not marry Mr Lidderdale, she was determined no one else should.”

The Central Somerset Gazette reported that William’s brother believed the mysterious Miss Vining was an English West Country girl who probably came from the Shepton Mallet area. This threw attention back at the two Julia Vinings, from Shepton and nearby Westcombe. But there were a number of inconsistencies. Previous clues — the obituary notice and the handwritten book dedication — had used the initials BAH Vining, not J Vining. The mysterious Miss Vining was variously described as a wealthy American or a “Creole” with Spanish heritage. The Shepton Julia Vining was born in Wiltshire — although her mother was American. The Westcombe Julia Vining was born in Somerset and so were her parents. And how could a factory worker or a household servant have owned a yacht?

Census records show no BAH Vining anywhere in England around the time of William’s disappearance. There is one BA Vining, but she was only five years old at the time of the disappearance. Genealogical records throw up a lot of false leads. Records for Somerset and Kent (where William was said to visit Miss Vining and her yacht, and where the cedar box turned up) show no individuals matching the age profile.

The most remarkable lead turns out to be a remarkable red herring. This is an obituary dated 10 November 1912 for “Miss William Robertson Vining Lidderdale Hasledean” who died aged 40 in Ilminster. On face value, it would appear that Miss (Beatrice Hasledean) Vining has taken William Roberston Lidderdale’s name, presumably through marriage. Improbably, the record shows another person on the record as Miss Elizabeth Chapman — William’s jilted bride. Had Miss Vining married William and somehow ended up living back in Ilminster with Bessie? No.

After extensive investigation, the supposed obituary turned out to be an American newspaper article about the Lidderdale case, which had been confusingly mis-indexed with a very misleading merging of names. But there is another lead worth chasing, and it takes us back to Shepton Mallet. If we cannot solve the mystery of the missing William Lidderdale, perhaps we can find out what happened to the missing Julia Vining…

Back in Ilminster in 1945, the Daily Mail reporter finished a brief conversation with the elderly Bessie Chapman. Census records are only available up to 1921, but at that time, she was still single and living with her aunt’s family in Ilminster in a grand building known as Bay House (which is now a listed building). Her occupation was listed as “home duties”, and census records also show that she lived by “private means” — perhaps from her aunt’s family or perhaps from William. In addition to the £500 she had received after his disappearance, had she possibly managed to cash out his life insurance policies or access his bank balance and shares?

In any case, Bessie was left to shoulder the mystery of William’s disappearance. “I never saw Willie again,” she told the reporter. “I often wonder what happened…”

Next week: The Belle of Shepton. The story continues. If you haven’t already, subscribe for free to get the complete story delivered to your inbox.

Missed the previous instalments? Find them here:

Recommended

TV: Say Nothing (Disney+ UK)

Yes, we’re watching The Day of the Jackal (on Sky/NowTV in the UK), which is very good up to a point (with Eddie Redmayne channelling Tom Cruise’s Ethan Hunt as much as Edward Fox’s Jackal). But you’ve no doubt heard a lot about that, so I’m recommending Say Nothing, an adaptation of the Patrick Radden Keefe book about the Troubles in Northern Ireland, focusing on the 1972 “disappearance” of mother-of-ten Jean McConville and the involvement of Provisional IRA volunteer Dolours Price. It’s gripping and revealing on a complicated subject that mainland Brits tend to know too little about. It’s a nine-episode series streaming on Disney+ in the UK and Hulu in the US.

Article: Ben Mezrich’s Foolproof Formula for Hollywood Success (Vulture)

Simon van Zuylen-Wood meets “one of the most bankable writers in the business” in this fascinating profile. When I wrote my first book, The Rocketbelt Caper, Ben Mezrich’s Bringing Down the House was a big influence. Not in terms of subject matter (The Rocketbelt Caper is about a fiercely-feuding team of jetpack builders; Bringing Down the House is about a card-counting MIT blackjack team) but in terms of being the kind of propulsive, cinematic page-turner I wanted to write. I didn’t realise at the time, but I was writing IP: intellectual property suitable for Hollywood adaptation. Bringing Down The House became the movie 21. (The Rocketbelt Caper has yet to become a movie, although it has been under option for most of the 20 years since it was first published.) Mezrich’s subsequent books have all been adapted, and he sells proposals to Hollywood before he writes the books. He’s also embraced a divisive “hybrid” fiction/non-fiction writing style in which he invents dialogue and scenes — something that most non-fiction writers (including myself) would never do. “My dream was never to win the Pulitzer Prize or the National Book Award,” he says. “It was to have the paperback come out with the little thing that says NOW A MAJOR MOTION PICTURE.” You can read the article here.

You can get Bringing Down The House on Amazon. The book that Mezrich relied on as his writing bible is Writing the Blockbuster Novel by Albert Zuckerman, which you can also get on Amazon.

The Rocketbelt Caper is also available on Amazon. You can read more on my website. Here’s what a magazine that doesn’t exist anymore said about it:

I’ve added Say Nothing, Bringing Down The House, Writing the Blockbuster Novel, and The Rocketbelt Caper to the Singular Discoveries bookshelf.*

News

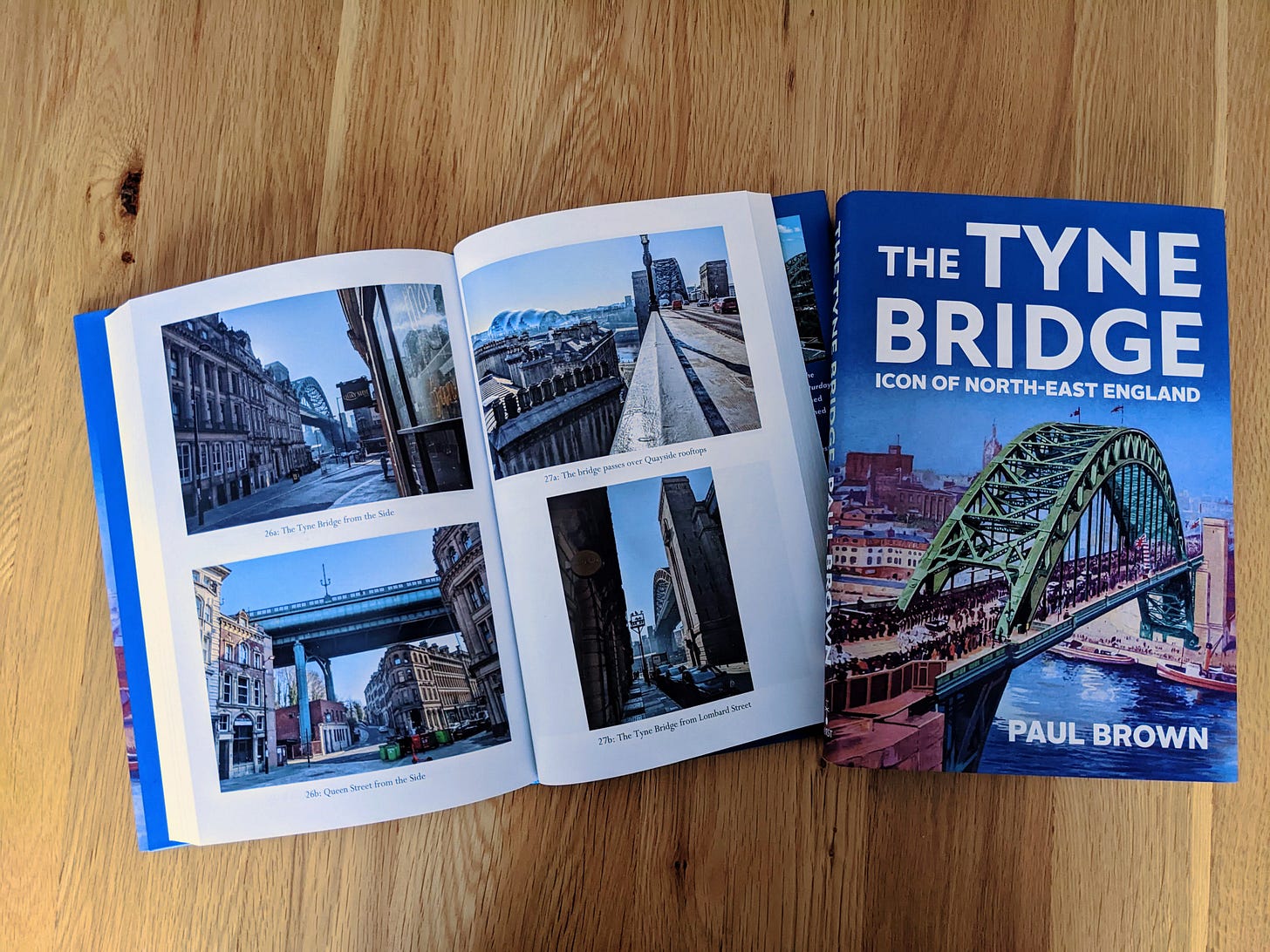

Reminder: My publisher Hurst has 50% off all titles in a Black Friday sale, meaning you can get the 2024 paperback edition of my latest book The Tyne Bridge for just £6.50. Offer valid until 2 Dec 2024; the discount is applied automatically at checkout. You can get the offer here.

The Tyne Bridge celebrates 100 years of one of Britain’s most iconic structures. Linking Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead, it has become a symbol of Tyneside, an emblem of the region’s cultural identity, and a monument to the Tyne’s industrial past. It’s “lavishly” illustrated and would make a fantastic Christmas gift, even if I do say so myself.

Also:

My Narratively article The Great British UFO Hoax was republished by the Smithsonian Magazine.

My article about the future (and past) of Newcastle United’s St James’ Park is in the December 2024 issue of When Saturday Comes.

I’m no longer on Twitter/X, but I’m on Bluesky: paulbrownuk.bsky.social

More next week. The conclusion of the vanishing bank manager mystery will hit inboxes in just seven days’ time. (Then we’ll go back to our regular monthly schedule. Too much of a good thing, etc.) Please share and subscribe.

*This publication features Amazon affiliate links. If you use them, I may receive a few pennies to help fund the newsletter. See our Amazon bookshelf here.