The Mysterious Miss Vining

The Vanishing Bank Manager part 2; PLUS dark web kill list, and a haunted museum

In the previous edition of Singular Discoveries, we searched for the missing bank manager William Lidderdale, who vanished a few days before his wedding to Bessie Chapman in 1892. Lidderdale’s disappearance was linked to a mysterious woman known as Miss Vining, and her yacht, the Foresight…

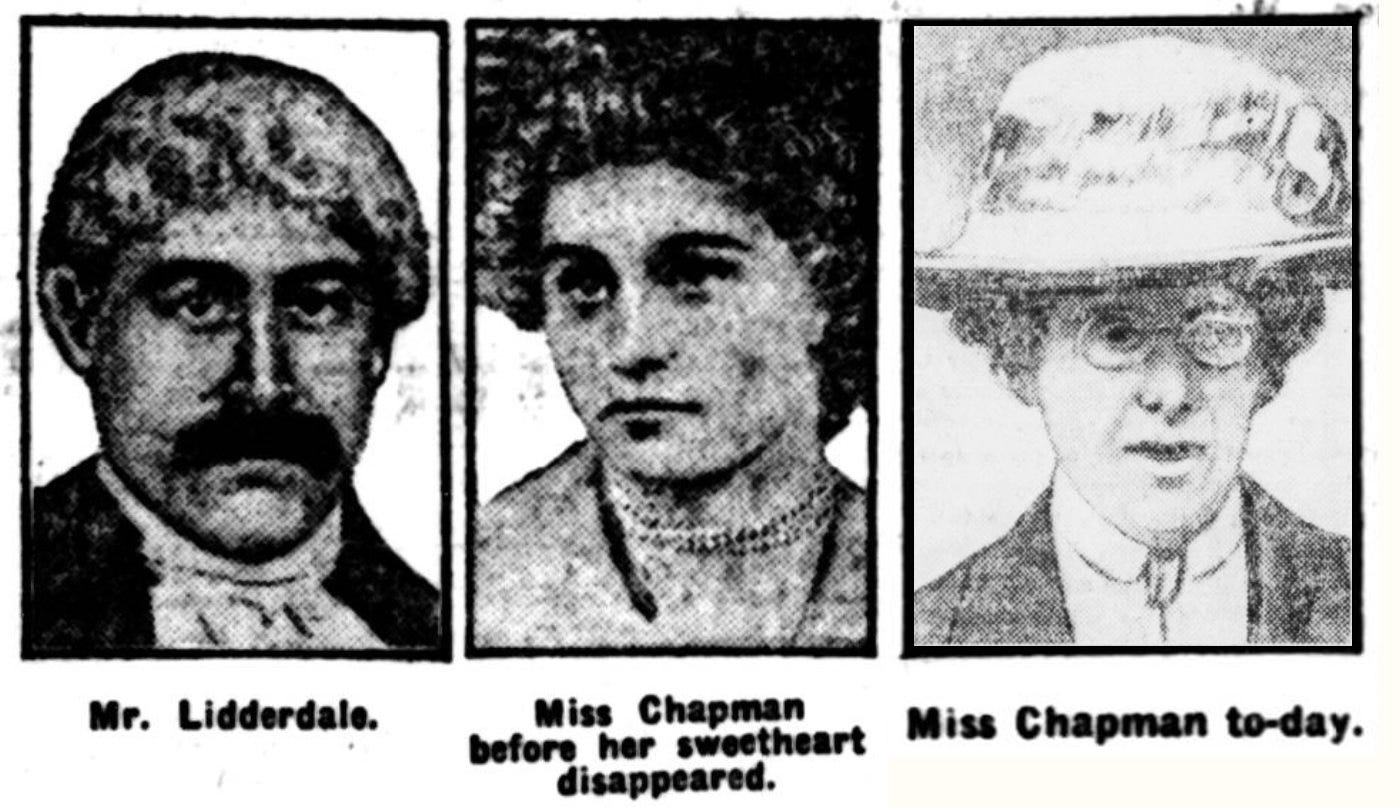

Bessie Chapman stood in the court wearing a dark grey outfit with a pink tie and a straw hat trimmed with ribbon. It was May 1913, more than 21 years after the disappearance of her fiancé, the Ilminster bank manager William Robertson Lidderdale. Bessie was now 41 years old and still unmarried. She lived in the Somerset market town with her uncle and aunt. William had held two life insurance policies worth £1,000 each, and Bessie was the named beneficiary. But, to claim the insurance, she would need to prove he was dead.

This was the seventh time the case had been brought before the probate court, but it was the first time Bessie had appeared to give evidence, which generated particular interest in the press. The judge, Mr Justice Bargrave Deane, was less enthusiastic about revisiting the matter. When Mr Pridham Whippell, the solicitor supporting the application to presume death, began to remind the court of the circumstances of the death, the judge responded, “I know the whole story by heart. What is the good of your going over it all again?” But, Mr Whipell said, certain particulars had never before been presented to the court, and he wanted to dovetail those into the story.

So Mr Whippell recounted how, in January 1892, just days before his marriage to Bessie Chapman, William Lidderdale travelled to London for a work meeting and never returned. William sent Bessie a letter from London mentioning meeting a Miss Vining. Several days after his disappearance, an obituary appeared in the London newspapers stating that William had been injured in a carriage accident and had subsequently died on Miss Vining’s yacht, the Foresight. And several days later, Bessie received a package containing £500 in bank notes, a Christmas card she had previously sent to William, a Jubilee coin that had been William’s keepsake, and visiting cards printed with Miss Vining’s name. On the back of one of the cards was written, in William’s handwriting, “Was true to you.”

First, Whipple said, efforts had been made to trace the bank notes, and £200 worth of them had come from an agent of Stuckey’s Bank — of which William was a branch manager. The remainder had not been traced, and Whipple noted it was not customary for Stuckey’s to keep such a large number of notes at their branches. But the counterfoil of the cheque that William used to withdraw the cash bore the words: “£1,000 Crew’s property; £20 self.” Mr Crew was William’s client in London.

Whipple said that William had intended to return from London, and had purchased a return ticket. But Whipple said that William had been in “a most precarious state of health”. According to his brother, William was suffering from diabetes, which, in 1892, was a fatal disease with no known treatment. (Victorian doctors diagnosed diabetes by tasting patients’ urine for sweetness.)

Crucially, Whipple had information about the mysterious Miss Vining. Some years before his disappearance, William had told friends about Miss Vining and showed them a photograph of her. And William had given his sister a cheap “yellowback” novel titled Lost For Love, in which both William and Miss Vining had signed their names. According to several reports, Miss Vining’s name was written as “Beatrice Alice Hazledean Vining”. If this was her full name, it matched the BAH Vining from the obituary and the visiting cards.

There was also new evidence regarding Miss Vining’s yacht, the Foresight. Although there was no such vessel recorded in Lloyd’s Register, the chief coastguard at Westgate-on-Sea, near Margate, on the Kent coast, stated that he knew the vessel and that it had been lying at anchor off Westgate in September 1890. If the vessel was not registered with the Lloyd’s in Britain, it could have been registered in another country.

Further to that, George Hitchins, who was William’s cousin and worked as a bank manager in Westgate, stated in an affidavit that William had been staying in Margate in September 1890, and had visited him in Westgate. William’s arm was in a sling, and he said he had dislocated it in a carriage accident while driving a Miss Vining. This was 15 months before his disappearance, but, if true, it firmly tied William to Miss Vining and her yacht — and preempted the story of a carriage accident.

“I have never doubted the existence of the yacht, nor have I doubted the existence of Miss Vining,” responded the judge. “I couple the two together as reason for this gentleman’s disappearance. The case is becoming clearer and clearer each time it is reopened.”

Bessie was cross-examined by Mr Bernard, the solicitor for the two insurance companies. “She is of medium height, has a healthy open-air complexion, and wears spectacles,” said one newspaper. It was reported that she gave Mr Bernard a pleasant smile as she responded to his questions. Asked when she first heard of Miss Vining, she replied, “I cannot remember.” She had never met her, nor seen a photo. But Bessie did confirm: “He told me about her and that she wished to marry him.” According to Bessie, William had met Miss Vining in Bath after he picked up her hat, which had blown off in the street.

“When you became engaged to be married in 1890, did he tell you that he had given up his acquaintance with Miss Vining?” asked Bernard.

“I understood from him that she would not interfere with us at all and that there was nothing to be afraid of,” replied Bessie. As far as she knew, William had not seen Miss Vining between the date of the engagement and the day of his disappearance. And she could not recall William mentioning seeing Miss Vining in Westgate. “I don’t remember,” she said. “This was so long ago.”

Then the judge inquired if Bessie had ever asked William where Miss Vining lived. She had not.

“But ladies are very curious about this sort of thing,” said the judge. “Don’t you remember him telling you who Miss Vining was or where she lived?”

“I trusted him and asked very little about her,” said Bessie. “I remember I was told she had a very bad temper.” There was laughter in the court.

Bessie had heard that “there was Spanish blood in her”, and understood that she was part Spanish and part English (although gossip had suggested she was American). Some newspapers labelled Miss Vining as a “Creole”, which at the time was a term for someone who was born in the Spanish-speaking parts of the Americas or West Indies.

“What occurs to me,” said the judge, “is that this gentleman met this lady in London and was inveigled into her yacht and, without intending it, was taken away with her.”

Bessie seemed to nod her agreement. Her final words before she left the witness box were, “I regard Mr Lidderdale as an honourable man.”

The next witness was Albert Brookes, William’s friend and colleague at the Ilminster bank, who was now his executor and trustee. Brookes said he knew of William’s friendship with Miss Vining and the story of how they had met, although he said the hat incident occurred at Midsomer Norton railway station, not Bath. He understood that Miss Vining had, on more than one occasion, asked William to marry her. He believed her full name to be Beatrice Alice Hasledean (or Hazeldean) Vining. She was supposed to be American and about 40 years old. She was “very eccentric” and wealthy and owned carriages, horses, and — of course — a yacht.

Brookes said he had spent 21 years following up every possible clue to find his friend.

“Do you believe this man died on January 30, 1892?” asked the judge.

“It was generally believed, and I believed so at the time,” said Brookes

The judge was clearly frustrated. “Mr Brookes wants me to give him leave to swear that the man is dead when he is not quite sure of it himself,” he said.

The hearing would need to be adjourned again while further inquiries were made. In particular, the judge wanted to hear from the solicitors of Mr Crew, William’s client. William’s letter had intimated that these solicitors had told Miss Vining of his arrival in London, so they must have known Miss Vining. But he warned Mr Whipple not to bring the case back to court until all sources of inquiries had been exhausted.

As far as records go, it appears that Mr Whipple did not bring it back. So, the final verdict was that of Mr Justice Bargrave Deane — William had met Miss Vining in London and “without intending it”, was taken away on his yacht.

There were other theories, of course. Some believed that neither Miss Vining nor the yacht existed and that William had invented them to get out of his wedding. But Robert Berryman, William’s neighbour, didn’t think that was true. “The whole story of his disappearance is far too romantic for him to have invented it,” said Berryman, “for he was a practical, unimaginative man.”

One of the solicitors involved in the case, Mr Langford, said he had received new information that suggested William was dead. According to Langford, William had confided to a close friend “certain facts which constituted strong reasons why he should not go through with the marriage.” Langford said he could not disclose those facts, but he believed that William was “passionately fond” of Bessie. “My own personal view,” said Langford, “is that he felt he could not honourably retire from his engagement and that, in the special circumstances, the only way out was to take his own life.”

So, was Miss Vining a figment of his imagination or a real contributing factor to William’s “special circumstances”? Certainly, newspaper reporters believed there was a Miss Vining, and they attempted to identify her. In fact, improbably, they identified four Miss Vinings, all of whom might have had connections to William Lidderdale. But did any of these Miss Vinings have anything to do with his disappearance? And was there any truth to the rumour that one of these Miss Vinings had also disappeared around the time that William vanished?

In 1937, 45 years after the disappearance, crime writer David Hume, author of the Mick Cardby series of pulp detective novels, wrote about the case and provided his verdict. “Satisfied that he had made some provision for the unfortunate Miss Chapman,” wrote Hume, “knowing that by his association with Miss Vining his financial future was assured, maybe glad to break away from the social life of a small town, and the monotony of a country bank manager’s life, Lidderdale changed his name, probably married Miss Vining, and passed from the sight of those who knew him to start a new life.”

Then, in late 1945, shortly after the end of the war, an unusual clue was found in a cellar in Hythe, Kent. Fifty-three years after William Lidderdale’s disappearance, what was the significance of the mysterious cedar box?

Next week: The Cedar Box. The story continues. If you haven’t already, subscribe for free to get the complete story delivered to your inbox.

Recommends

Podcast: Kill List (Spotify)

Journalist Carl Miller was investigating the dark web when he made the disturbing discovery of a secret “kill list” on a murder-for-hire website. The website was a scam designed to relieve the hirers of large bundles of cryptocurrency. So there were no dark web assassins involved, but the fact remained that the hirers were trying to have people killed. Armed with this information, Miller is placed in the difficult position of having to contact the potential victims and try to convince them that someone wants them dead. It’s a gripping listen. You can find it wherever you get your podcasts.

Article: Are Ghosts Haunting the British Museum? by Killian Fox (1843 Magazine)

I missed this fascinating piece about strange occurrences that revolve around the British Museum’s huge inventory of weird and wonderful exhibits when it was first published in 2020. If anywhere is haunted, it is surely a place with loads of removed (and stolen) artefacts and dead bodies. You can read it here.

News

My article The Great British UFO Hoax has been republished by the Smithsonian Magazine, the journal of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, under the title How British College Students Convinced Authorities That Flying Saucers Were Invading the UK. Originally published by Narratively, this is a true story about a 1967 alien invasion that wasn’t quite what it seemed. You can read it here.

I have a new football article in the latest edition of When Saturday Comes magazine about the future (and past) of Newcastle United’s St James’ Park. Titled James Bond, it looks at the potential implications of the club moving away from the ground it has called home since 1892. That’s in the December 2024 issue of WSC, number 448, which you can find at good newsagents or buy online here.

For those interested in football, and particularly Newcastle United, I was interested to note that the club appears to be making moves to acknowledge the year 1881 as its official foundation date. The club was founded in 1881 as Stanley FC and changed its name in 1892 to Newcastle United. However, since the 1990s, the club has erroneously marketed 1892 as the foundation date. Hopefully the missing 11 years will soon be restored. I wrote a book about the club’s early years, All With Smiling Faces. You can read more and get the book here. As noted by my mate Ant, it might make a very good Christmas present…

My publisher Hurst has 50% off all titles for Black Friday, meaning you can get the 2024 paperback edition of my latest book The Tyne Bridge for just £6.50. That’s Christmas sorted… Offer valid from 18 Nov to 2 Dec 2024; the discount is applied automatically at checkout. You can get the offer here.

In case you haven't seen it, here’s a video trailer for the book:

More next time. Please share and subscribe.

Another great historical story from Paul