Thirty-Two Days Adrift

A fight for survival in shark-infested waters; PLUS palaeontology and plane crash

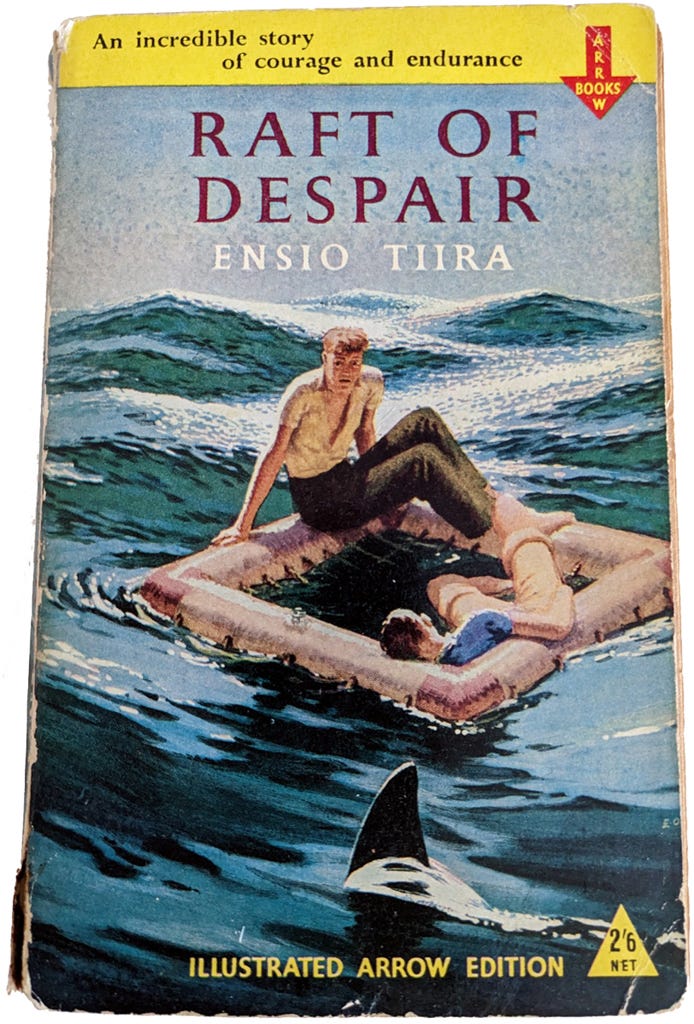

Ensio Tiira was alone on a tiny raft in the middle of the Indian Ocean. He was starving, weak, and delirious. The tropical sun was punishingly hot, the raft was falling to pieces, and the ocean was broiling with a shiver of sharks. “If I have ever been certain of anything in my life,” he recalled, “it was that on my thirty-first day at sea, I was about to die.”

It began with a map. Tiira was aboard the transport ship Skaubryn, sailing from North Africa to Southeast Asia. It was February 1953, and Tiira and his colleagues were reinforcements for the French Foreign Legion fighting in Tonkin, North Vietnam. A fellow Legionnaire named Fred Ericsson grabbed Tiira by the arm and showed him the map. “Can’t you see it, Ensio?” said Ericsson. “This is it. This is where we escape.”

For Tiira, a 24-year-old Finnish recruit, the Legion had seemed like his escape from an unhappy home and a broken marriage. But now, like many legionnaires, he wanted out — before they reached the war zone. By then, it would be too late. According to Tiira, “Legionnaires, even indifferent ones like ourselves, didn’t run away in a fight.”

Ericsson was a Swede who had sailed the Indian Ocean before. His plan was simple. Pointing to the map, he showed Tiira how the Skaubryn would skirt within a few miles of the northern tip of Sumatra. If they took one of the ship’s lifeboat rafts and paddled for an hour or so across the calm sea, they would easily reach Sumatra and freedom.

At 3 am on the morning of 23 February 1953, Tiira and Ericsson lowered their raft into the ocean and leapt after it into the darkness. It was a tiny vessel, a red and white square with grab ropes around the outside and canvas strips across the floor. They drifted away under the night sky and watched the Skaubryn’s lights disappear. Then their plan began to fall apart.

Ericsson had injured his hip in the leap, and Tiira had to paddle alone. They dropped a wine bottle containing their only liquid overboard and drifted off course in the scramble to retrieve it. Then they watched the lights of the Skaubryn reappear as the ship doubled back. Their escape had been discovered.

A searchlight beamed across the surface of the water. The ship came closer. Four hundred yards. Tiira and Ericsson crouched low in their raft. One hundred yards. Then, suddenly, the searchlight went off. “The ship was just beyond us now,” Tiira wrote. “Troops lined the decks and we could see them staring out across the water. But they were looking ahead not behind. They had missed us.”

When the sun came up, the Skaubryn had gone. A shoal of fish had gathered under the raft. Then came the first of the sharks – three of them, including a ten-footer. One of the sharks barged into the raft and almost knocked Ericsson overboard. Tiira bashed it as hard as he could across the head with his paddle. The sharks withdrew, their fins still visible in the raft’s wake. The men paddled until sunset. There was no sight of land.

Tiira asked Ericsson, “Are you sure we were off Sumatra?”

On the second day, Tiira and Ericsson ate their only food and drank the last of their wine. Ericsson’s injury had worsened and he was unable to paddle. There was still no sign of land. Glimpses of ships in the distance gave them hope, but SOS signals with a flashlight brought no response. By the third day, as a storm brewed, the situation became desperate. “Oh god! What fools we had been to leave the ship,” wrote Tiira. “How long could we endure this?”

It was not Tiira’s first encounter with mortal danger. In 1944, as a sixteen-year-old army volunteer, he was on a raft that overturned in a Finnish lake and was saved from drowning by a friend. In 1949, he was a deckhand on a ship that caught fire and was one of the last men to reach the lifeboats. And then there had been his first escape, in 1939, when he was evacuated from his village amid bombs and mortar fire during the brutal Russian invasion.

Now, as the hours turned into days, Tiira recognised: “Death this time was the final escape.”

Tiira and Ericsson clung to life by drinking drizzles of rainwater. They sucked on unlit cigarettes and smelled the cork of the empty wine bottle for comfort. Tiny crabs appeared in the bottom of the raft, but they provided minuscule amounts of meat. All the time, more sharks, bigger and closer, circled the raft. The sharks would feast on the shoal of fish, battering the raft and churning the ocean.

On what was perhaps the fifth day adrift, there was a great ripping of canvas, and a shark’s head burst through the bottom of the raft. “I jabbed at it with the end of the paddle, and all the while Ericsson was hitting it too. Another lunge, I felt, would bring the brute right through the raft and send us into the water. But thank god it sank back and out and away.”

Tiira and Ericsson began to argue, blaming each other for their predicament. Ericsson, becoming delirious, accused Tiira of attempting to push him overboard. Their voices became hoarse and faded to whispers. But occasionally, Ericsson would muster the energy to sing a sea shanty. Tiira found this incredibly moving. Despite their disagreements, their shared experience meant Ericsson was the best friend Tiira had ever had. But Tiira knew that both men would soon die.

Ericsson whispered to him, “We should try to live for two weeks.”

Tiira replied, “Without water, we can’t live for another two days.”

Ericsson did live for two weeks. But by the fifteenth day, he was slipping out of consciousness. Tiira tried to ask him about his background: “About your family, if something happens to you…” Ericsson said his home was in Gothenburg, but nothing more.

At about noon on the seventeenth day, the rain came that Ericsson needed to keep him alive. “Here’s the rain, Ericsson,” called Tiira. “This is what you’ve been waiting for.” But Ericsson didn’t respond. “Ericsson, wake up.” Tiira felt for his friend’s pulse and found that he was dead.

“For Ericsson, the agonies of escape were over.”

Tiira had promised to bury Ericsson on land, so he kept him in the raft. “I felt he was my friend still and it was a comfort to have him with me,” he wrote. But Ericsson’s body quickly decomposed in the tropical conditions. The tiny crabs in the bottom of the boat began to eat away at the dead man’s flesh.

On the twenty-fifth day, eight days after Ericsson had died, they came for him – ten sharks, three of them the largest Tiira had ever seen, perhaps three times longer than the raft.

The sharks swam against the raft’s sides and came up underneath it, striking it with fearsome blows. They lunged over the sides and lurched up through the floor. Tiira lashed at them with his paddle but felt helpless. “I was spent and horribly afraid. What more can I do? A dying man can’t fight sharks.”

Tiira knew that to have any chance of saving the raft, he needed to throw Ericsson’s body overboard. As the sharks attacked, tilting the raft into the air, Tiira heaved his friend’s body over the edge and into the sea. “They got Ericsson with a yard of the raft and, fighting among themselves, lashing and churning, they took him away.”

Slowly, the raft drifted far from the terrible scene. “I tried not to look at the sea where it boiled and flashed. Pieces of clothing were scattered over a wide area. I was safe on my broken raft. The sharks were all with my friend.”

Over the next few days, Tiira edged closer to death. His mouth was full of sores and his body was covered in ulcers. Rain came, but he couldn’t drink. Ships passed, but he couldn’t signal. The sharks returned, sensing another meal. “I was getting weaker every day. And I knew it.”

One night, as Tiira wished for a peaceful death in his sleep rather than waking to face another hellish day, his fitful dreams were interrupted by the noise of something large moving through the water. His subconscious jolted him awake. It was a ship, just twenty yards away. He tried to shout, but had no voice. He waved his shirt, but it was too dark for anyone to see. The ship came right alongside the raft, and Tiira — summoning the last of his strength — grabbed his paddle and clanged it against the metal hull.

After a short while, a searchlight began to sweep across the water. The ship circled, and the searchlight swept closer.

“And suddenly, it was alright. They found me. A great beam of light came straight on my face and I sank down on my knees and knew it was over.”

The ship was the British freighter Allendi Hill. It was just after 3 am on 27th March, 32 days almost to the minute since Tiira had left the Skaubryn. He was picked up about 300 miles from Sri Lanka, some 600 miles from his supposed destination at the northern tip of Sumatra.

The crew treated his wounds and allowed him small amounts of water and food. And the captain promised he would not turn him over to the Foreign Legion. Instead, the ship took Tiira back past Sumatra to Singapore General Hospital.

Once he had recovered, as he waited for passage home on a Finnish tanker, Tiira wrote a book about his experiences. “Epätoivon Lautta” was published in English as “Raft of Despair”. It is dedicated to Fred Ericsson. ♦

The Dog and the Dinosaur coverage

Following the publication of my story The Dog and the Dinosaur, about Leicester Stevens and his dog Laddie and their search for a brontosaurus in the Congo, both the Telegraph newspaper and BBC Radio 4 picked up the part about Leicester’s granddaughter Dr Lil Stevens, who is a palaeontologist at London’s Natural History Museum.

As the Telegraph removed mention of my story as its source in their website edition (and didn’t restore it when requested), I’ve no qualms about providing a link to their otherwise very nice article that allows you to leap over the paywall. Read it here.

BBC Radio 4 ran an excellent interview with Lil about the story on the Woman’s Hour programme. You can listen again here (from about 47 minutes in).

Oh, and the line the Telegraph website cut was: “Paul Brown’s story ‘The Dog and the Dinosaur’ is available online.” Here’s a clipping from the paper edition:

Death of an Angel trailer

The trailer for The Dog and the Dinosaur seemed to generate a lot of interest, so here’s one for my previous story, Death of an Angel:

In case you missed it, you can read Death of an Angel here.

Now a quick recommendation:

Recommended

Lost in Shangri-La by Mitchell Zuckoff (Book, 2011)

In 1945, before the end of the Second World War, a US Army plane crashed into an uncharted valley on the island of New Guinea. There were only three survivors, but they were not alone — the valley was inhabited by warring native tribes. Mitchell Zuckoff’s book tells the gripping true story of the daring mission to rescue the survivors from this lost world they called Shangri-La. It’s no surprise that the movie rights for the story have been snapped up. (Unfortunately, Doug McClure is no longer around to star.) In the meantime, you can watch documentary footage shot during the rescue mission. You can get the book here.*

You can find all our book recommendations on the Singular Discoveries Amazon shopfront.*

See you next time. Please subscribe and share the joy.

Thanks for reading this free newsletter. You can support Singular Discoveries by sharing it with friends. You can also browse my books or buy me a coffee / make a small one-off contribution. Just click here. — Paul.

Ads: I’m obliged to say that links marked with an asterisk (*) are affiliate links. If you use them, I may receive a small payment to help run this free newsletter.

Another fascinating story from Paul.