The Dog and the Dinosaur: Deleted Scenes

Extra good stuff from the brontosaurus hunt story; PLUS The Beatles at Stowe and the Klondike Gold Rush

Last week I posted my latest true story, The Dog and the Dinosaur, about Captain Leicester Stevens and his rescued war dog Laddie and their $5m quest to find a living brontosaurus in the Congo. If you missed it, you can read it here.

Although it’s a feature-length read, there wasn’t room to fit everything in, and lots of good stuff was left out. That’s never a bad thing. I like to trim the fat from my writing to make it as lean as possible. But sometimes fat is tasty. So here’s a small selection of interesting bits and pieces that ended up being cut (plus some unused artwork and photos). I hope it enhances your enjoyment of the story:

The Famous Golfer

Leicester Stevens first found fame as a talented amateur golfer. He was taught the game as a boy by his father and later by the Scottish professional Peter Paxton, and he developed a prodigiously long drive. Leicester entered the British Amateur Golf Championship at Prestwick in 1911. Described as the “dark horse of the tournament”, he eliminated the famous Abe Mitchell in the quarter-finals, to the delight of a large crowd.

In his semi-final, Leicester met former champion Edward Lassen and was leading until he had two holes controversially awarded against him – first for grounding his club while taking a swing in the rushes, then for putting while his caddy was still standing on the line. After Lassen rather unsportingly claimed the disputed holes, the crowd jeered him and fully supported Leicester. But Leicester was visibly unsettled by the incidents, and Lassen came back to win.

Leicester appealed to the Championship Committee – something frowned upon at amateur tournaments – but the appeal was rejected. Lassen went to the final, where he lost to Harry Hilton, and Leicester went home. Reflecting on a fine tournament, one newspaper said Leicester was “manifestly upset by his unpleasant experiences”.

After Leicester went to Africa, his quest was reported in the golf press at home and abroad. In early 1920, American Golfer magazine reported: “Well-known golfer Captain LB Stevens recently started on a journey into the wilds of Africa in order to find the mysterious brontosaurus. Lack of space prevents our describing this interesting animal and the desirability of finding him.”

The War Hero

Leicester began his military career as a teenager in the British Army’s Royal Field Artillery Territorial Force. When the war began, he was in China, working as a consulting engineer in Peking (Beijing). “At Kitchener’s summons, back he came,” says his son Philip Stevens, “like they all did, like idiots.”

After training, Leicester volunteered to join a Royal Field Artillery Brigade attached to the 14th (Light) Infantry Division and was appointed Staff Captain. The 14th (Light) was involved in the war’s deadliest battles, at Ypres, the Somme, Arras, and Passchendaele. At the Somme in 1918, the 14th (Light) lost almost 6,000 men, and its artillery brigades lost all their guns. By the war’s end, the division had suffered more than 37,100 casualties.

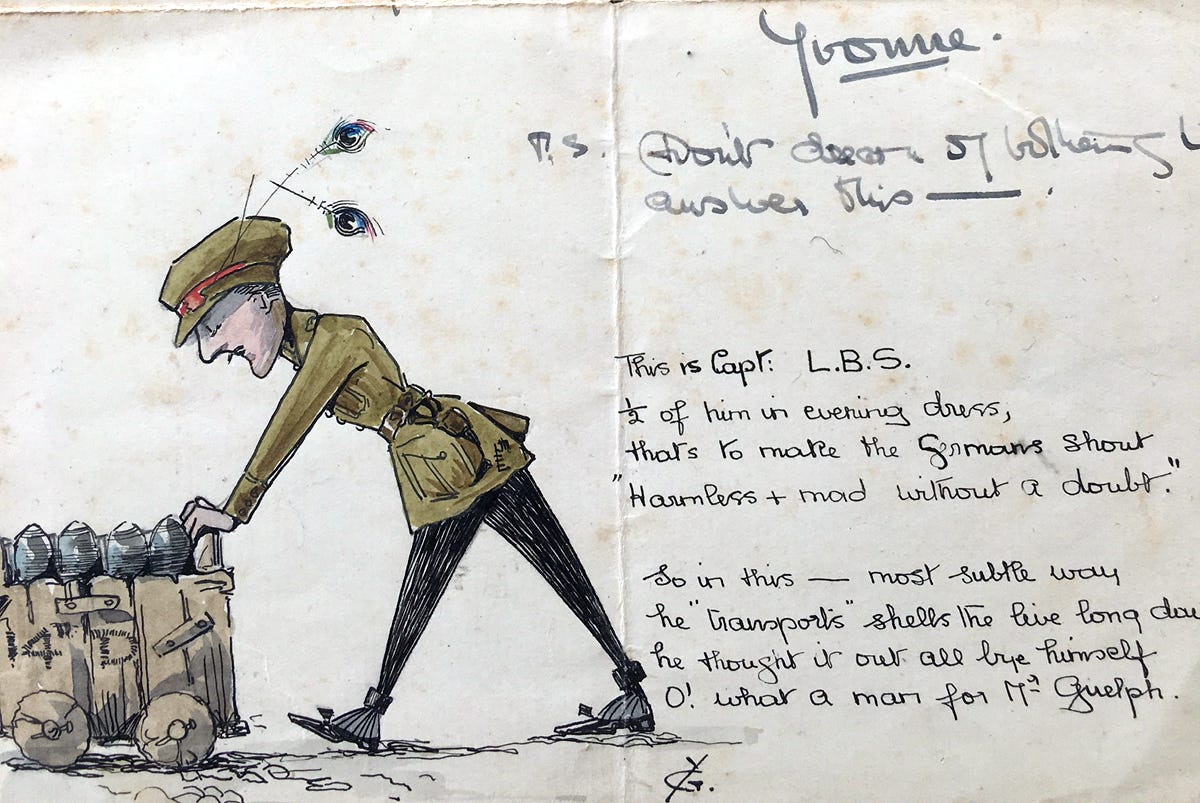

In August 1918, while Leicester was taking part in what would end up being the final Allied push, his sister Yvonne sent him a letter. “My dearest old Leck,” she wrote. “I’m afraid you’re having a strenuous time. I only wish I could send you out a safe comfy house and beautiful bed, you poor old thing.” She included a sketch of the moustachioed Leicester pushing a trolley full of mortar shells while wearing his military jacket with formal black trousers and shoes, and with peacock feathers in his cap. “This is Captain LBS; Half of him in evening dress; That’s to make the Germans shout; ‘Harmless and mad, without a doubt.’”

The War Dog

During the final advance in August 1918, Leicester found the war dog he named Laddie. The opposing sides used more than 16 million war animals during the First World War, including several thousand dogs. Laddie was a German barrage dog, used to carry messages between the front-line infantry and the artillery. According to one story, Leicester found Laddie on the battlefield sitting on the dead body (or, in one telling, the scattered remains) of his German master. Another story said Laddie wandered across into the British camp during the fighting.

At the end of the war, many animals were disposed of to avoid the cost and effort of repatriation. Horses and mules were sold to French and Belgian farmers, or to abattoirs for “humane slaughter”. British war dogs were sold off for around seven shillings each (around £16 or $22 today). Many German war dogs were retrained as guide dogs for blinded soldiers. Others, like Laddie, were taken back to Britain. Some were allowed to travel officially, subject to proper quarantine requirements. Others were smuggled back by their adopted owners in troopships.

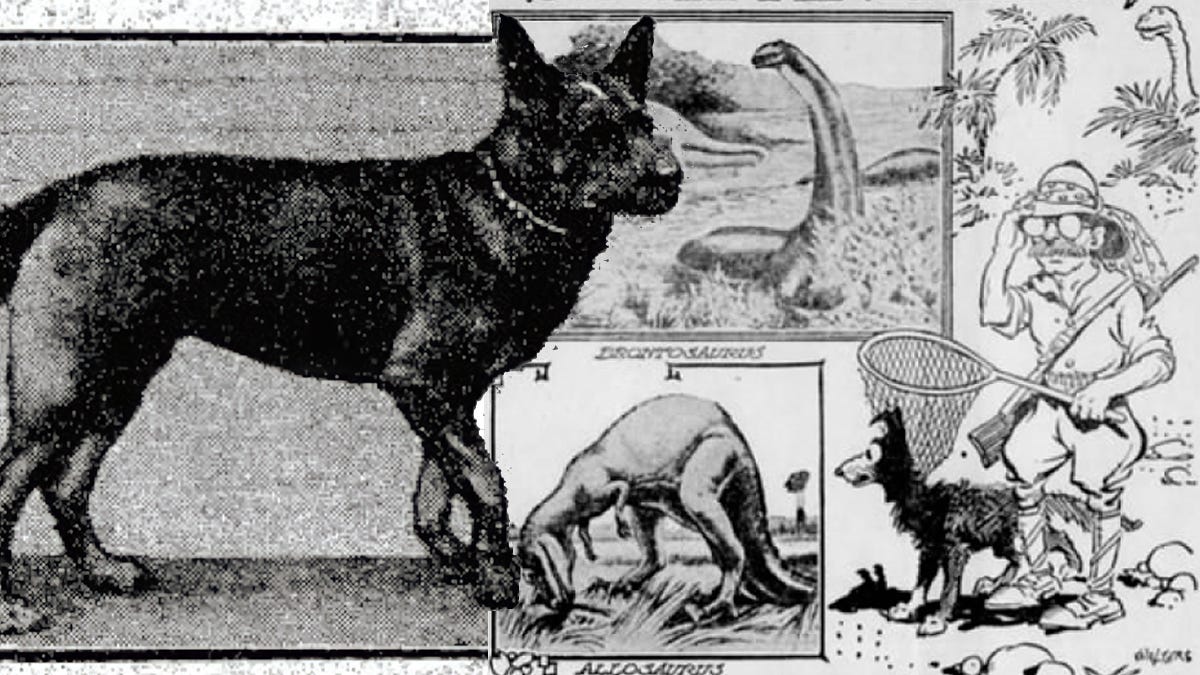

Laddie was described as “partly sheepdog, partly wolf”. One fanciful story, in the London Weekly Dispatch, said, “Laddie’s mother was an Alsatian sheepdog who had in her time padded out to the wood and married a wolf, returning to the farm for the birth of her offspring.” Photographs indicate he was a German Shepherd or Alsatian. Known for their strength and intelligence, German Shepherds were vital allies, particularly as the human death toll soared and manpower became increasingly scarce.

During their training, war dogs were said to display a keen sense of humour and ridicule. The dogs rested during the day and trained at night. According to Lieutenant Colonel EH Richardson, who operated a war dog training school for the British military, groups of highly-trained dogs would watch groups of new recruits being put through their paces with “indignation and contempt” and hurl “loud choruses of derision”. When the experienced dogs got their turn they would “delight in showing their prowess and superiority”.

The Ruins

At the end of the war, Leicester obtained a camera and took a series of startling photographs showing the ruined wasteland. Philip Stevens describes them as “a lot of very horrific photographs of poor old France at the end of the war. The unbelievable ruins. Ypres Cathedral and stuff like that.” Also among Leicester’s photos was a shot of a war horse inscribed with the message, “The best horse I had in France”, indicating that Laddie was not Leicester’s only war animal.

The Sightings

For the British press, the reported sightings of an extraordinary creature in the Congo only strengthened a belief in the survival of “certain monsters of the prehistoric age” in unexplored regions of Africa. The Times of London referenced a quotation from Pliny the Elder: “Semper aliquid novi Africam adferre” (“Africa always brings us something new”).

Although the creature was categorised in the media as a brontosaurus, initial witness Monsieur Lepage said it had a long, pointed snout “adorned with tusks” and a horn above its nostrils. Subsequent witness Monsieur Gapelle described the creature as having a very thick tail, a horn on its snout, a hump on its back, and scales running down its body.

Shortly afterwards, a Congo correspondent of the Bulaywo Chronicle reported that the monster had charged through a village and destroyed the majority of its huts. “That put the tin hat on it,” wrote the correspondent. “We had to go out on Saturday to kill the beast.” Unfortunately for the correspondent, and fortunately for the dinosaur, the government intervened, ordering that the creature should not be molested, with the threat of a heavy penalty.

The Reward

The Daily Mail estimated the creature’s weight at between 80 and 90 tons, or almost three times the weight of the Mark V tank that had smashed through the Hindenburg Line during the final months of the war. The newspaper added, “And future explorers who seek to encounter it might be wise to take a tank with them for that purpose.”

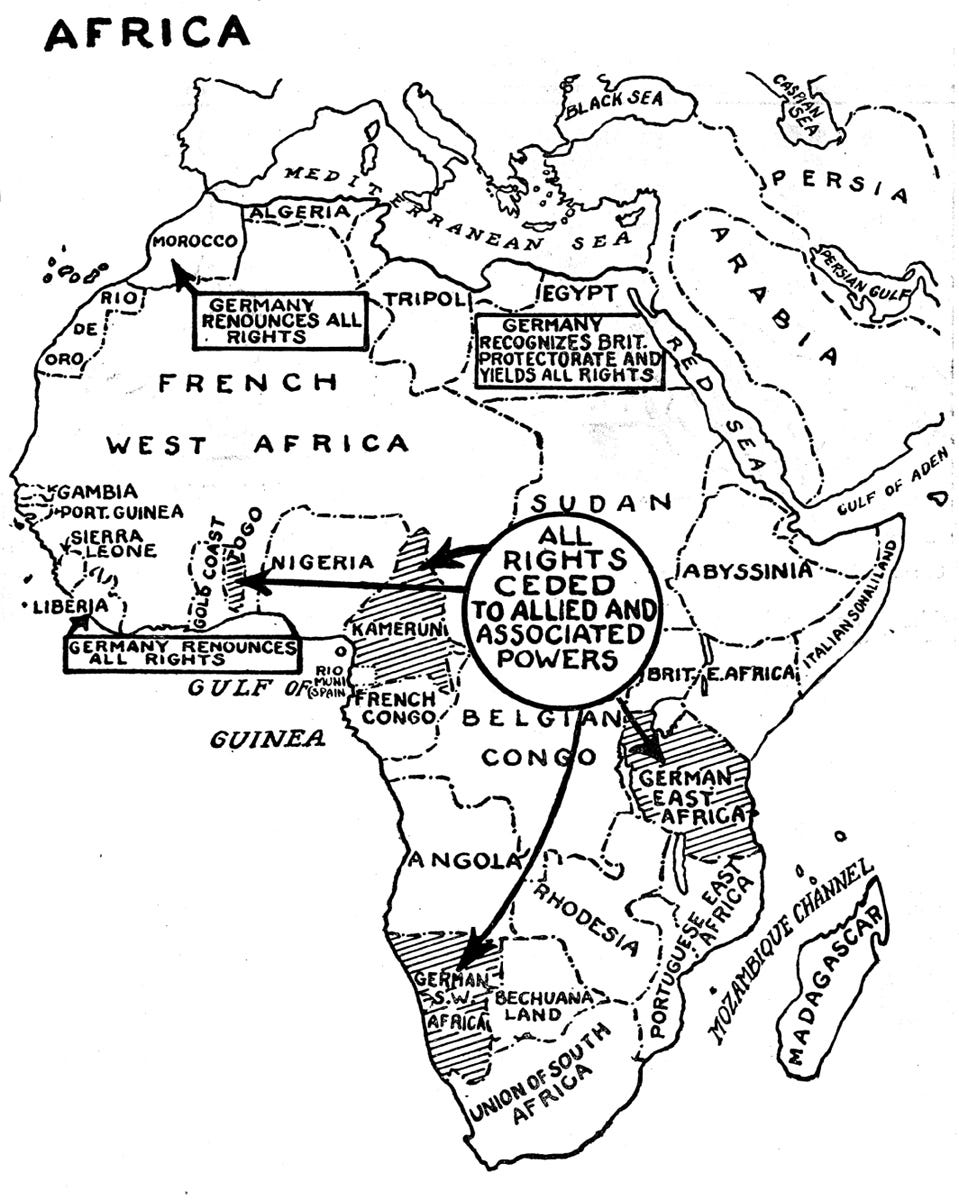

It was the Mail that first reported the reward for the capture of the dinosaur. “The American Smithsonian Institute has offered £1,000,000 to anyone who will bring him to them,” said the newspaper. A million pounds was worth five million dollars in 1919, and has a relative inflated worth of about 80 million dollars today.

As the report was not true, it could be said that the Daily Mail caused the ensuing “dinosaur frenzy”. The newspaper has a history of involvement in monster hoaxes. In the 1930s, the Mail was involved in the search for the Loch Ness Monster, and in the 1950s it sponsored a £1m hunt for the Himalayan Yeti.

The Experts

Walter Winans, the famous American big-game hunter and Olympic deer-shot champion said: “I do not think it is impossible that some of the prehistoric animals have survived, and when several explorers have seen glimpses of what they think must be such animals they are most probably right.” And John Daniel Hamlyn, the London-based naturalist and exotic animal dealer, said: “I have been there and I have talked to natives who will not pass a certain boundary into ‘evil land’ because of the huge monsters which live in its remote solitudes.”

However, more scientific observers were skeptical. Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchell, secretary of the Zoological Society of London, said it was possible that a brontosaurus might be living in the Congo, “but I feel safe in offering a thousand pounds to a half-penny that it is not.” Chalmers Mitchell did relate the tale of the former Kaiser, Wilhelm II, who, on a pre-war visit to London Zoo, described an encounter with a “similar prehistoric monster” in German East Africa.

Chalmers Mitchell later said the basis for the brontosaurus story was probably a large deposit of fossilized dinosaur remains that had recently been found in Tanzania. He was en route to the excavation site to supervise the excavation of the fossils and “protect them in the interest of British science.”

Another interesting insight came from Ernest Schwarz, a professor of geology and the editor of the Scientific African magazine. Schwartz said he first heard of the creature from a surveyor in Northern Rhodesia, who witnessed huge footprints that had been preserved by locals with fences. “I have actually seen it in the field,” he said, “not in the flesh, but as it lay buried in the earth.” Inspired by the pre-war discovery of many fossilised dinosaurs at Tendaguru in Tanzania, Schwarz had led an expedition from Port Elizabeth and found the 60-foot-long skeleton of a sauropod, later identified as an algoasaurus - a cousin of the brontosaurus.

Impassioned Appeal

“Since the story of my search for the brontosaurus was first told in the Daily Mail,” Leicester told reporters on his departure from London, “I have been inundated with letters from officers and others wanting to take part in the search. One dear old lady wrote four pages of impassioned appeal for the great reptile’s life to be spared when I should encounter him. She added that she had long been a member of the Wild Birds’ Protection Association.”

Close Encounters

Mr CG James of Swansea sent an account of an enormous creature that inhabited the swamps on the borders of the Katanga district in the Congo and was known to locals as the “chipekwe.” William Carrington from Leamington Spa said he had been told by a Belgian explorer that there was a huge lizard-like creature, larger than any other animal ever seen, living in the Congo.

The most vivid report came via John Alfred Jordan, a noted adventurer and big game hunter. According to Jordan, he was hunting near the Migori River in present-day Kenya when his native “boys” reported that a strange beast was drinking from the river. Jordan grabbed his hunting rifle and pushed through the foliage towards the water. First he saw a huge footprint and then, as he reached the river, he saw the creature – and instantly fired at it. According to Jordan, the creature was 18-feet long with a scaled body, a head like a lion, and two “fangs” like a walrus. The locals called the animal the “bingoeck” or the “nuquta”.

The Smithsonian Expedition

In June 1919, a party of explorers, scientists, and motion picture producers set off from New York for Central Africa as part of the Smithsonian African expedition, jointly funded by the Smithsonian Institute and Universal Pictures. Officially, the expedition was aiming to capture movie footage and photographs of unusual zoological species. Unofficially, the expedition would hunt for the brontosaurus.

The expedition’s leader was Smithsonian zoologist Edmund Heller, a noted expert in African mammals. The man in charge of the film production was Hollywood leading man William “Bill” Stowell, a handsome matinee idol who had starred in almost 120 silent movies, including The Heart of Humanity with Dorothy Phillips and The Talk of the Town with Phillips and Lon Chaney. The expedition’s business manager was Dr Joseph R Armstrong, a Los Angeles dentist.

Several months into the expedition, news emerged from Africa of a terrible tragedy in which several members were severely injured and both Bill Stowell and Joseph Armstrong were killed. Initially, reports were vague. Excited implications suggested the incident involved a dinosaur. Eventually, it was revealed that there had been a terrible rail accident in the Congo. A detached railway car had smashed into the expedition’s carriage.

Stowell sustained a fractured spine. It took more than 24 hours to get him to hospital in Elizabethville, where he died. According to the LA Times, the death of Bill Stowell, the “immensely popular” screen player, “saddened the world.”

A Farm in Rhodesia

Although Leicester travelled to Africa on board the SS Llanstephan Castle on Christmas Eve 1919, he is not listed among the ship’s regular passengers. Instead, he seems to be among 110 “Government passengers” who were travelling on a colonisation scheme sponsored by the Rhodesian government. “Proof has been given in Rhodesia that the British genius for colonisation is as vigorous as ever,” said the Pall Mall Gazette.

The scheme provided subsidized passage and a package of land for British workers who wished to settle in the colonies. Military veterans received special consideration. This suggests an alternate motive for Leicester’s journey to Africa. He seems to have been traveling to Rhodesia to start a new life – with the dinosaur hunt an attractive bonus. Rhodesia was, according to one report, “full of opportunities, but be sure you are the right man or woman for those opportunities before you go.”

When Leicester was eventually located in Rhodesia, he was found to be living on a farm that he had built, with his new wife Elizabeth. Philip believed that his father might have married Elizabeth Moolman on the ship during the voyage. He was told this story by his niece, Sarah McNair, who is Elizabeth’s granddaughter.

Sarah is a former London theatrical agent who now lives in Tarn-et-Garonne in southwestern France. Sarah says Elizabeth was returning home after the Great War. She was South African, but had been sent to school in England, and had remained there until the war when, still in her 20s, she worked as an ambulance driver in France. Sarah describes her grandmother as an intriguing and alluring figure. “She was quite flamboyant,” Sarah tells me. “She smoked a cigarette with one of those holders.”

Elizabeth had lost both her mother and sister in a terrible accident — the Blaauwkrantz Bridge disaster of 1911 — when their train fell into a gorge. Her brother survived with two broken legs. As her father was already dead, she and her brother inherited the family’s farm at Somerset East, Cape Province. Elizabeth sold her share to her brother, and was quite wealthy. “I think he married her for the cash,” says Sarah. “He had a farm, but there was nothing on it. He was expecting her to stock it for him. She said to me, ‘He was just a gold digger, my dear.’”

Sarah was told that Leicester and Elizabeth were married on the Llanstephan Castle by the ship’s captain. There might have been some form of ceremony, but records show the couple were not officially married until July 1920 — with Leicester’s second wife May (Philip’s mother) as a witness.

The Hoax Revealed

By the time Leicester reached Africa, the brontosaurus mystery had been solved. South Africa’s Rand Daily Mail published a letter forwarded by a Mr James McIntosh revealing the origin of the hoax. “It is all a yarn,” wrote the correspondent. The supposed witnesses “Monsieur Lepage” and “Monsieur Gapelle” were pseudonyms created by a gentleman named Dave Le Page. Le Page had invented a monster story to pull a visitor’s leg. The visitor relayed the tale to the press, and it became a worldwide sensation. “The story has caused a lot of amusement up here,” wrote McIntosh.

Further details emerged in the Rhodesian Farmer and Settler publication: Dave Le Page was an Australian engineer engaged at railway works near the foot of the mountain at Fungurume. One evening, he met an American drilling engineer named Mr Raymer, spun him a yarn about an encounter with a huge creature, and drew a sketch, which he placed on the engineer’s bed. The American related the story to a Mr Fitzsimmons of the Port Elizabeth Museum, who in turn informed the local press. The story – with various errors and embellishments – reached the London newspapers, and then went global.

1922, the Rhodesia Journal reported that a prospecting expedition led by Le Page, “the hero of the world-disturbing discovery of the brontosaurus”, had discovered a richly-seamed gold field in the Belgian Congo.◆

You can read the full story of The Dog and the Dinosaur here.

Now some quick recommendations:

Recommended

BBC Front Row: The Beatles at Stowe School (radio)

In April 1963, the Beatles played a gig at Stowe School. That much was well-known by Beatles obsessives. But what was completely unknown was that one of the pupils in attendance, 15-year-old John Bloomfield, recorded the concert on a reel-to-reel tape. Presenter Samira Ahmed was unaware of the recording when she decided to make a radio programme to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the gig, and even Beatles superbrain Mark Lewisohn had no idea it existed. (John had neglected to tell anyone.) The tape is rough but remarkable, the earliest known recording of a (almost) complete UK performance, capturing the last show at which the band could hear themselves play without being drowned out by the frenzy of Beatlemania. You can listen to the programme here.

Gold Diggers by Charlotte Gray (book)

I read this book around the time I was writing The Man Who Rode The Bear. Subtitled “Striking It Rich in the Klondike”, it’s the story of the Yukon Gold Rush, which began in 1896 (about half a century after the California Gold Rush featured in The Man Who…). Tens of thousands of prospectors travelled over the deadly Chilkoot Pass and up the ferocious Yukon River towards the remote frontier settlement of Dawson City, about 2,000km north of Vancouver. Charlotte Gray tells the story via the recollections of six Klondikers, including miner Bill Haskell, entrepreneur Belinda Mulrooney, and a young writer named Jack London. It’s a gripping page-turner, a survival adventure, and a fascinating history that will make you curious to visit Dawson — although probably not via the Chilkoot Pass. Get the book here.*

Gold Diggers is also available to borrow from the Internet Archive Lending Library, which is currently facing a fight for its future following a US court ruling.

You can find all our book recommendations on the Singular Discoveries Amazon shopfront.*

Until next time. Please subscribe and share with all your friends.

In case you missed it:

The Dog and the Dinosaur

Two days before Christmas in 1919, Captain Leicester Stevens, a British military officer, set off from London with his rescued war dog Laddie on a ten-thousand-mile journey into the unexplored heart of Africa to hunt for a dinosaur. There had been a flurry of reported sightings in the Belgian Congo of a huge monster, which witnesses identified as a bron…

Ads: I’m obliged to say that links marked with an asterisk (*) are affiliate links. If you use them, I may receive a small payment to help run this free newsletter.