Queen Victoria's Giraffe

Earth's tallest animal on a "veritable voyage of death"; PLUS special guest Daniel Gray on fish and chips

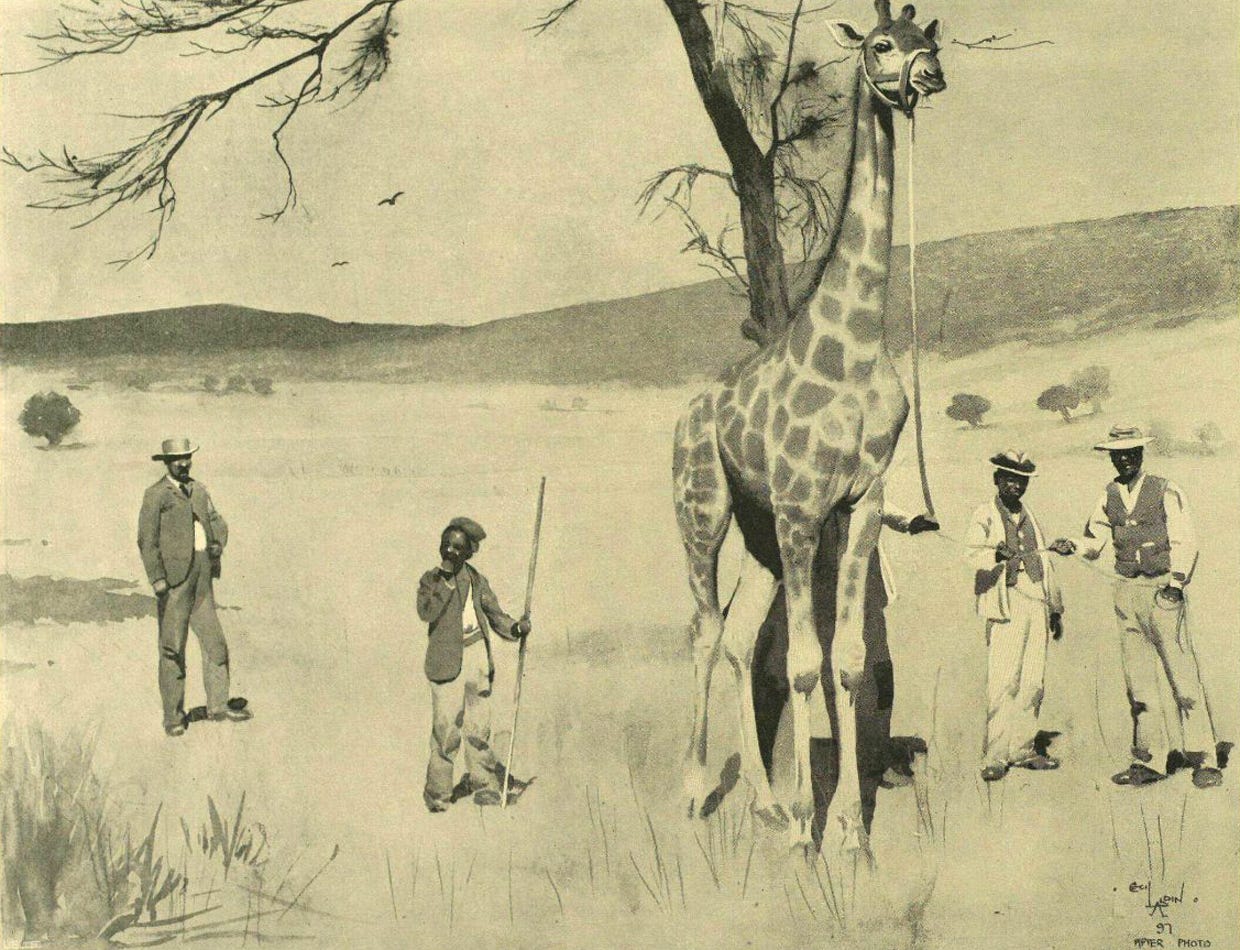

Sometimes, a picture’s caption says everything. That’s pretty much the case with this photo from the Illustrated London News in 1897. The caption reads:

“The giraffe presented to the Queen by King Khama on its native soil before the voyage to England, which ended in its death.”

A short paragraph on the previous page provides a little more detail. The giraffe was gift for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee and was intended for the Zoological Gardens, now London Zoo. “It was a particularly fine example of a species now rapidly becoming extremely rare, and ere long likely to be practically extinct,” said the newspaper, adding that “an inborn loathing of captivity” and “bad seamanship” had “made the journey to this country a veritable voyage of death”.

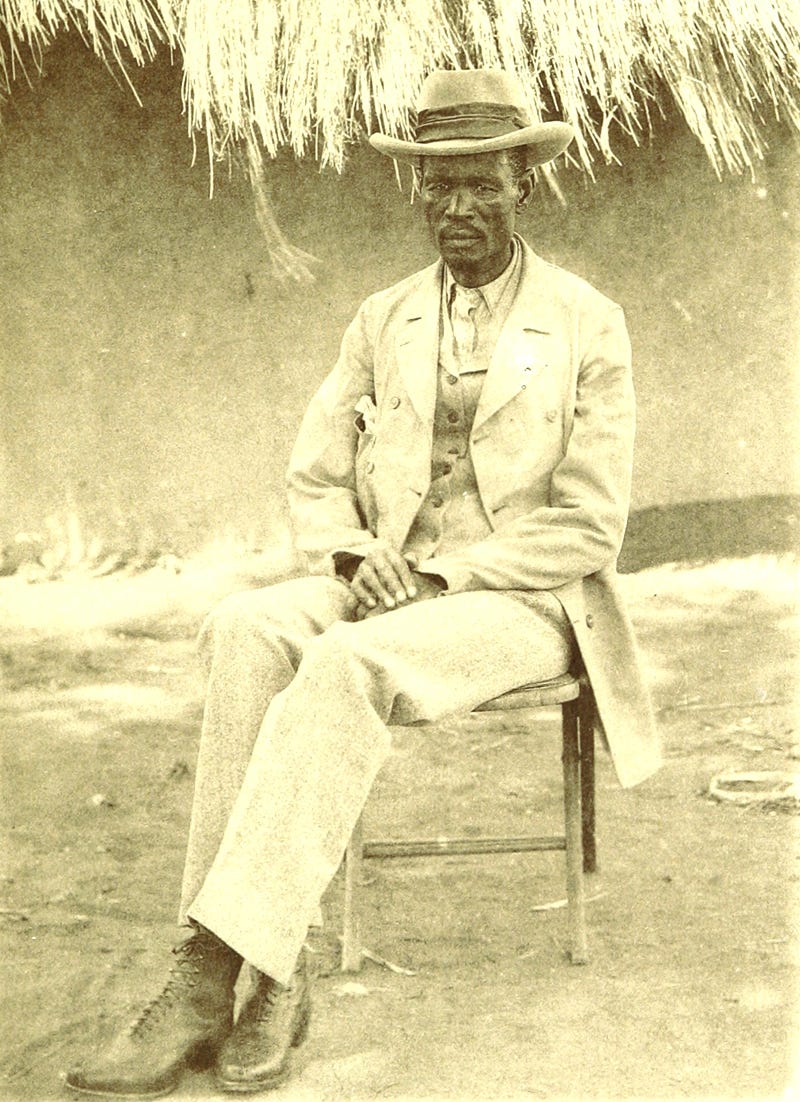

Khama III was the long-serving kgosi (supreme chief or king) of the Bamangwato or Bangwato people of Botswana. Khama became king after overthrowing his father Sekgoma, who responded with an assassination attempt and witchcraft. (It’s definitely worth reading his Wikipedia page.)

The giraffe, it seems, was jointly supplied by another Botswanan king, Bathoen I, the kgosi of the Ngwaketse people. At the time, Botswana was the “British” Bechuanaland Protectorate. (The Republic of Botswana was created in 1966.) It was also in the midst of a devastating famine. As a protectorate rather than a colony, local leaders were left to rule, although Victoria was the ultimate monarch.

The giraffe was a male, a “splendid specimen” standing 13ft tall. It was said to be “remarkably tame”. Hermann Windhorn, a German representative of the Zoological Gardens, collected the giraffe and walked it to a railway station, where it was placed in a box and transported to Cape Town. There, it was placed onboard the Roslin Castle, a Currie Liner. The liner set off for England on 1 September 1897.

Botswana is about 5,000 miles from the UK — as the crow flies. A sea journey via the South African Cape of perhaps 7,500 miles would take three weeks. A more detailed account, in London’s St James’s Gazette, makes clear why the creature might have struggled to survive.

It was impossible to accommodate a 13ft-high box, so the animal was packed using a “telescopic arrangement” in a crate that was only 8ft high. So, the giraffe would have to stoop its neck for the duration. We are informed, however, that “the interior was carefully padded, so as to save its inmate from being bruised by the motion of the ship”.

Bad weather was encountered on the voyage, and by the time the ship reached Cape Verde, about halfway to England, the giraffe was refusing food — even the ship’s baker’s “special brown bread”. At Madeira, after two weeks at sea, Herrman Windhorn sent a telegram to London stating his fear that the giraffe would die before it reached England.

A week later, the giraffe was unloaded at the East India Docks, on the Thames at Blackwall, London. Its huge packing crate was transported to the zoo in a Pickford’s removal van. Zookeepers used planks and rollers to unload and manoeuvre the crate. A crowd began to gather:

“News that something unusual was going on had spread among the visitors, and the space outside the barrier and along the side of the hippopotamus pond was densely packed.”

The keepers unlocked the gates to the giraffe enclosure and heaved the crate inside. A nervous silence fell upon those present as they watched carpenters work to unscrew the wooden boards that fastened the crate’s door. “It seemed as if the screws would never come out,” said the Gazette.

Eventually, the boards were removed. Clarence Bartlett, the superintendent of the zoo, opened the door and went inside the crate. Then he called for his assistant, Mr Thomson, to join him.

“The animal was lying down, with its neck bent out towards its right side,” reported the Gazette. “With that technical touch used only in those accustomed to handle animals, they felt the body and interchanged serious glances, which told the tale in a moment to those who were standing by the open door. The Queen’s giraffe was dead.”

Hermann Windhorn was in tears as he spoke to the press about the “beauty and docility” of the giraffe. The cause of death was not yet known, but the Gazette speculated that “the loss of appetite was a symptom of internal disease”.

The 7,500-mile journey by sea in a box was perhaps a more likely contributing factor. A post-mortem did later state that the giraffe’s “native health” could not stand the “hardships of ocean passage” and said he had been “a victim to that dread affliction: sea sickness.”

Newspapers described a melancholy that had settled over the zoo, where Clarence Bartlett was apparently roaming around “disconsolately”. “He had, in fact, already assumed quite a parental interest in the youngster,” said the Morning Leader, “for whom he had arranged a matrimonial contract with the dark orbed, graceful lady giraffe who has for some time past been in residence within the precincts of the zoo.”

In December, British diplomat Sir Alfred Milner met with King Bathoen in Botswana and “expressed Her Majesty’s sad regret at the sad event” of the death of the giraffe.

“But Bathoen,” said the Morning Leader, “was less concerned about the dead giraffe than about his living people, who were on the verge of starvation. They were very loyal, but they wanted food.”

“His excellency gave a most statesmanlike supply. That is to say, he expressed the government’s profound sympathy — but promised nothing.”

A century ago, there were perhaps a million giraffes in the wild. Today, according to the Giraffe Conservation Fund, there are approximately 117,000, with that number decreasing by around 10% every decade. According to the Born Free Foundation, there are more than 1,379 giraffes in captivity in the US and Europe, including 150 in the UK. The giraffe enclosure remains a popular attraction at London Zoo.◆

Now, here’s the Recommended section with special guest Daniel Gray.

Recommended:

Food of the Cods by Daniel Gray

I like football and I like books and I like fish and chips, and Daniel Gray has written about all of them. Food of the Cods: How Fish and Chips Made Britain is part travelogue, part social history, as Dan travels around the UK in an effort to understand the country’s often eccentric obsession with fish and chips, and the chip shops, chippys and fish bars that sell them.

Fish and chips is generally regarded as the UK’s national dish, although its initial popularity was largely due to Belgian and Italian immigrants. Brilliantly, even within the UK’s narrow shores, the dish is subject to a myriad of regional variations. Single or supper? Bits, scraps or batter? Bap, butty or barm? Salt and vinegar or chippy sauce? And do you want mushy peas or gravy or curry sauce with that?

In recent times, fish and chips has gone from being a working-class staple to something of a luxury treat, largely thanks to rising costs that have ravaged the industry. It’s a simple food, but proper preparation is a science. Good fish and chips can’t be bettered, but bad fish and chips are the worst of takeaways. (My own personal rule of thumb is to never get fish and chips from a shop that also sells pizzas and kebabs.) Luckily, as Dan finds, there are plenty of devoted chippy owners keeping the tradition very much afloat.

Food of the Cods is a mouth-watering celebration of F&Cs. I’m not sure any other book has ever made me so hungry.

Dan was kind enough to answer some quick questions:

Paul: What is it about fish and chips, despite heavy immigrant influence, that makes it a quintessential British national dish?

Daniel: If it is not some genetic need for batter – and I’m not ruling that out – I think it is the chip shops themselves. In their eccentricities, design, feel, smell and gossipy Friday queues they probably couldn’t happen anywhere else.

Paul: What’s the most surprising thing you discovered about fish and chips in Britain while writing the book?

Daniel: The amusingly trenchant strength of opinion people in this country have over such vital matters as which condiments and how much of them, accompanying drinks, the importance of scraps, fish types, skin on or off, curry sauce or not, is gravy on fish evil? and so on…

Paul: Can you recommend another non-fiction book that readers of Singular Discoveries might enjoy?

Daniel: Steeple Chasing: Around Britain by Church by Peter Ross is a beautifully-written, soulful book from a great writer.

Paul: Bonus question, for my own research purposes: Ever had decent fish and chips from a shop that also does pizzas and kebabs? I'm saying it’s impossible!

Daniel: Never. I completely agree. The simpler the menu, the better the fish and chips.

Thanks to Dan for his time. I’ve added Food of the Cods and Steeple Chasing to the Singular Discoveries Amazon Bookshelf.*

Oh, and if you’d like to listen to the audiobook of Food of the Cods, you can grab a free trial of Audible, which gets you one free audiobook to download and keep, or two free audiobooks if you have Amazon Prime. Just click here.

Brief news:

My Narratively Loch Ness story was included in the Longreads October “Monsters Among Us” reading list.

The Singular Discoveries podcast was featured in the November edition of Jack El-Hai’s indispensable Damn History newsletter.

Andrew Chapman’s excellent Histories newsletter featured a piece on Ambrose Crowley, the creator of the original English working-class society (from which I am descended), and a very complicated guy. I’ve got lots more to say about Crowley and his ironworks — for another time.

This Facebook trailer for the Titanic Rescue episode of the podcast has been pretty popular.

The Lintz Green stationmaster’s house from the second episode of the podcast is currently for sale.

In case you missed it, you can listen to the podcast here. There are three episodes so far.

Or you can listen to the entire series right now by becoming a podcast supporter.

Back next week with a new episode of the podcast, and next month with a regular newsletter. Thanks for reading.

Main sources: St James’s Gazette 21/09/1897, Morning Leader 22/09/1897 & 07/12/1897, Illustrated London News 18/12/1897.

*Amazon links are affiliate links. I may receive a small payment to help run this free newsletter if you use them.

What a forlorn story - but very interesting to read. And thank you for the mention!