Messages from the Sea

A note in a floating coffee tin tells a sad tale; PLUS 2023 preview: true crime, dinosaurs, grizzlies, whales...

One Thursday morning in late June 1899, an 11-year-old boy named William Andrews was playing on the beach at Ilfracombe in Devon, on the south coast of England. There he spotted a small tin floating in the water. The quarter-pound tin was marked “coffee and chicory”, and was tied up with a piece of cork for buoyancy. Inside the tin was a note, written in pencil on a page torn from a pocket diary. The note was signed by able seaman R Neel and was addressed to Mrs Abigail Neel in Cardiff, Wales. It read as follows:

“To my wife and children. The Stella is going down as I pen my last words. If I do not survive, go to my brother. Goodbye, my loved ones, goodbye.”

This was just one of hundreds of messages in bottles, boxes and tins washed up from the sea onto British and other shores in 1899, and one of thousands found during the busy Victorian and Edwardian steam and sail seafaring eras — an era before ship-to-shore radio, when a vessel lost contact with the world once it disappeared over the horizon. These messages from the sea told tales of foundering ships, missing ocean liners, and shipwrecked sailors, and contained moving farewells, romantic declarations and intriguing confessions. Some solved mysteries of lost vessels and crews, while others created new mysteries yet to be solved.

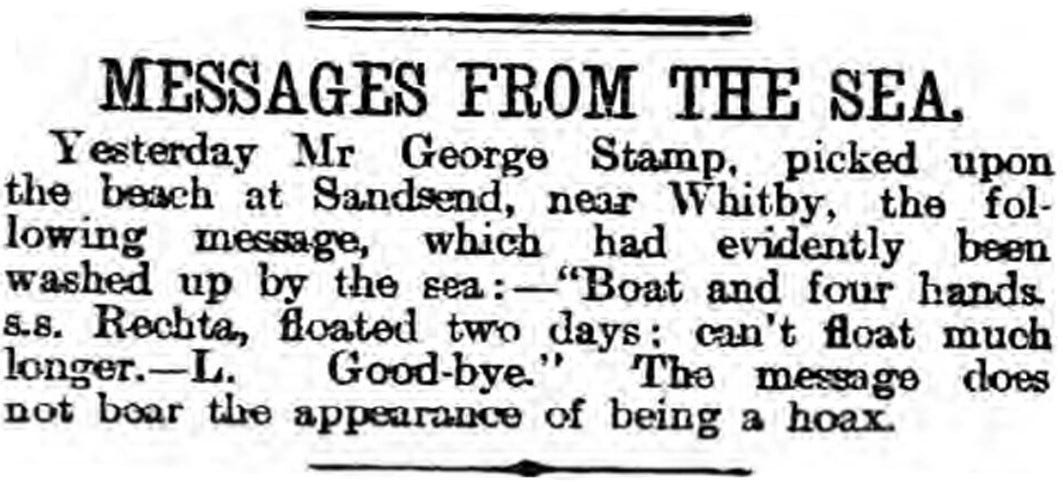

In some cases, these messages would be passed directly to family members. In others, where the recipient could not be identified, or perhaps at the request of the sender, they would be forwarded for publication in the press. The message found by William Andrews was passed to his local newspaper. It was published in the following day’s edition and, over the next few days, in scores of other newspapers across Britain. Messages in bottles were popular news items for the press of the day. Major newspapers such as the Times of London and the New York Times often printed such messages, as did hundreds of national and regional newspapers across the world. Some published them in regular columns, often headlined “Messages from the Sea”.

“Of all the tales of the sea,” remarked the Sheffield Evening Telegraph in 1893, “none are more pathetic than those which every now and again are related in curt language in the news columns of the daily press of the finding of messages written by those who far away at sea, the victims of some disaster, recognize the hopelessness of their position, and see on the horizon the dawn of eternity.”

The full meaning of able seaman Neel’s message became clear shortly after it was published. The Stella was a British passenger ferry that sailed between Southampton and the Channel Islands. It was wrecked in fog on the Casquets, north of Guernsey, in March 1899 with the loss of around 105 passengers and crew. No official passenger list was kept, and it was unknown whether an R Neel was on board. Inquiries made at the given address in Cardiff found that a man named Neel had formerly lived there, but “was supposed to have gone to Bradford”, where nothing else was known of him. Mrs Abigail Neel could not be traced.

For many seafarers, the message in a bottle was a legitimate and valuable method of communication, and perhaps their only means of contacting the outside world. Until the arrival of the wireless telegraph at the beginning of the 20th century, a ship that passed over the horizon and out of sight of land would lose communication with its home port for days, weeks, or months at a time. Perhaps another vessel might spy the ship on the ocean and return with news of its location. Or a letter might be carried from a far-off destination to advise of the ship’s safe arrival. But not all ships would arrive safely.

Seafaring was incredibly dangerous. Hundreds of vessels were lost at sea each year, perhaps overcome by waves, dashed on rocks, or engulfed in flames. A single storm could sink scores of vessels and wipe out entire fleets. Those that didn’t sink could be blown off course, become lost, and run out of food and water. Their crews might be left drifting in disabled ships, floating in lifeboats, or clinging to pieces of wreckage.

In such desperate situations, thoughts would inevitably be of family and loved ones at home, perhaps hundreds or thousands of miles away. A brief message, written swiftly in the most hopeless of circumstances, might include a desperate plea for help, but would more likely comprise a tragic goodbye. Often, after disasters at sea, messages in bottles were considered to be what Chamber’s Journal in 1880 called “the means of communication between the living and the dead”.

In 2016, I published a book titled Messages from the Sea, which collected 100 of these waterlogged notes. I also published more messages on a (short-lived) blog. The book was very well-received. The poet Ian McMillan recommended the “lost and found language of messages from the sea” as “superb” and a “fine read”. The composer Clive Whitburn wrote and recorded four pieces of music based on his favourite messages. BBC Radio Ulster’s Stephen McCauley created a soundscape inspired by the book. There were national newspaper spreads and international magazine articles. These lost messages seemed to touch people across the world.

Since writing the book, I’ve continued to collect these messages and their related stories. In 2021, I wrote here on Singular Discoveries about the Stella disaster (actually twice), during which able seaman Neel sent the message mentioned above.

You can find the Messages from the Sea book here:

You can read about the Life-and-Death History of the Message in a Bottle at Medium.

So that’s Messages from the Sea, but what about Singular Discoveries? We’ll be back in two weeks with something big and brand new — an explosive true crime tale.

There’s lots more to come in 2023, including a real-life dinosaur hunt, adventures with grizzlies and whales, and a new website linked to exciting TV, film, and podcast stuff.

Catch you next time, and please remember to share and subscribe.

Thanks for reading this free newsletter. You can support Singular Discoveries by sharing it with friends. You can also browse my books or buy me a coffee / make a small one-off contribution. Click here. — Paul.

Very interesting Paul. Keep the stories coming!