Forgotten on Death Row

The haunting tale of Charles Douthitt's endless wait for execution; PLUS new IP picks

Charles Douthitt was a killer. That much is certain. On Christmas night in 1916, he shot and killed his best friend, William Vernon Simms. Douthitt and Simms worked as tobacco strippers on farms near Georgetown, Kentucky. Douthitt was 19, and Simms was 18. The two teenagers had been out drinking and began quarrelling over politics. They were riding in a buggy on a country road and spilled out onto the ground in a brawl, during which Douthitt fired his gun. He quickly telephoned the Scott County sheriff and confessed his crime. He said he was intoxicated and did not know what he was doing.

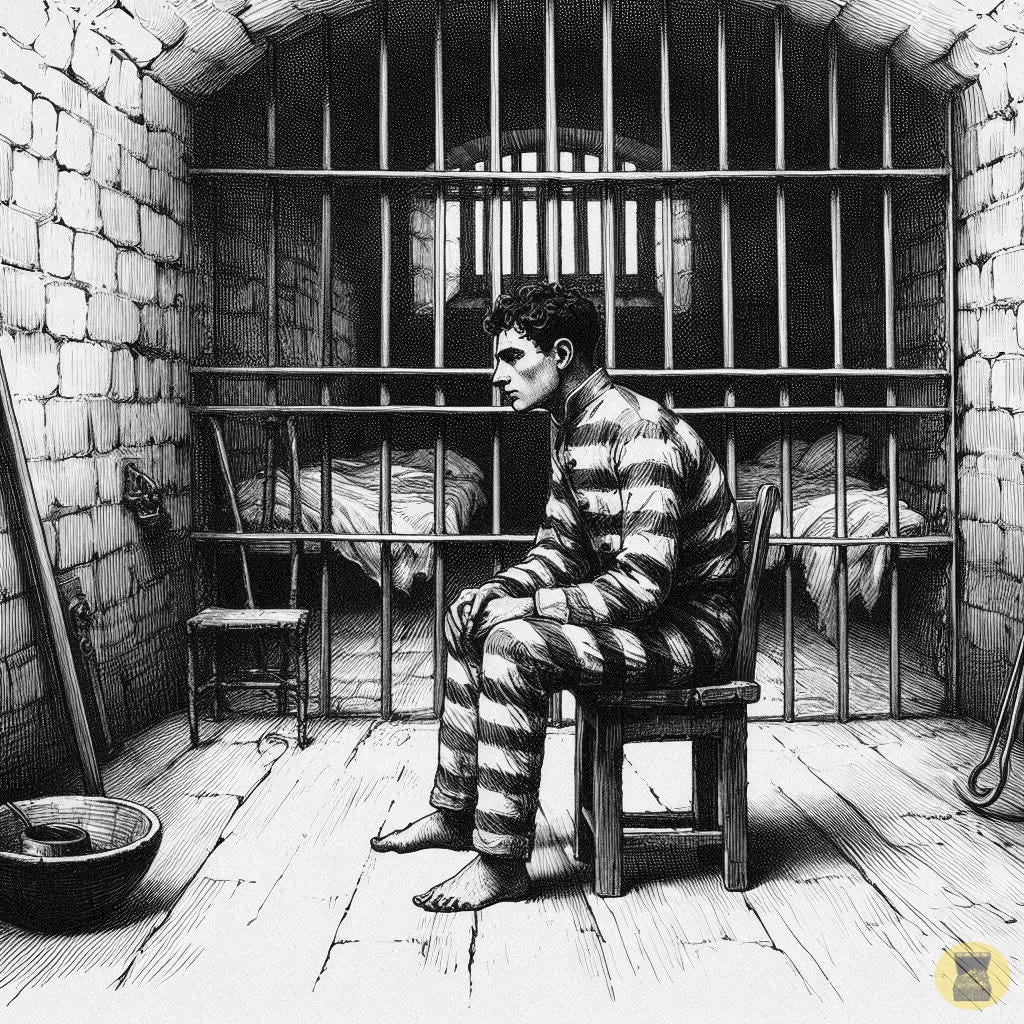

Douthitt was tried six months later, in June 1917. The prosecuting attorney was Church Ford. The defence attorney was John Ford, Church Ford’s brother. At noon on Wednesday, 13 June, a jury found Douthitt guilty of murder in the first degree. He was sentenced to be “destroyed in the electric chair” and ended up on Death Row at the Eddyville Prison. He was placed in a tiny cell in a narrow hallway, just a few feet from the execution chamber. And he waited to meet his fate. And he waited. And he waited.

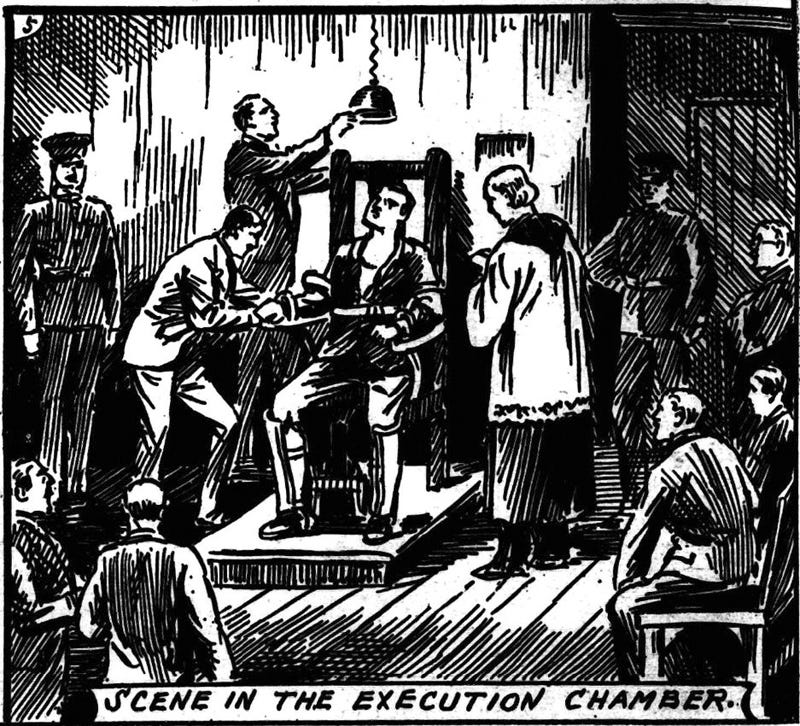

Douthitt watched through iron bars as the other inmates of death row — some of them the nearest thing he had to friends — were taken from their cells and led to their deaths. He listened to the hum of the dynamos and the crackle of voltage that accompanied their last breaths. And he waited. For years. Most inmates lived on Death Row for just a month or so before their sentence was delivered. But his turn never came. Because Charles Douthitt had been forgotten. He was a dead man waiting.

Charles T. Douthitt was born in Woodford, Kentucky, in March 1897. His family lived at Paynes Depot in the adjacent Scott County, about six miles from Georgetown and about 15 miles east of state capital Frankfort. He was one of four children — he had a younger brother, and an older brother and sister. He grew into a strapping youth. At the age of 20, when he was found guilty, he was over six feet tall and weighed 195 pounds (88kg).

On the night after he was sentenced, according to one newspaper, Douthitt attempted to commit suicide by drinking poison. He failed, and his death became the responsibility of the state of Kentucky.

Shortly after his sentencing and before being transferred to Eddyville, Douthitt escaped from the Scott County Jail at Georgetown. Douthitt and two other inmates overpowered prison officer Jack Lusby as he opened the door to their cell. Lusby was “disarmed and beaten up badly”. The prisoners fled through the rear of the jail and across a creek. Possees went after them with bloodhounds.

Douthitt slept in a haystack, then walked to his parents’ home at Paynes Depot. His mother made him some food. Then Douthitt called the sheriff and gave himself up. “I wanted to get home just once more and eat a home-cooked meal, as only my dear old mother knows how to prepare,” he said. “I wanted to talk to my parents just a little while before I gave up my life. I am ready now. Come and get me.”

Eddyville Prison, now the Kentucky State Penitentiary, was built in 1884. Its original limestone block buildings resemble a medieval castle, and its position on the Cumberland River gives it its nickname: the Castle on the Cumberland. The electric chair was installed in September 1910. At the time of Douthitt’s incarceration, Eddyville housed 457 prisoners.

Douthitt arrived on 20 August 1917. He secured a stay of execution for 60 days to appeal his case. The appeal dragged on and ultimately failed. In March 1918, the Court of Appeals affirmed his sentence, and his death warrant was sent to be signed by the Kentucky state governor, Augustus O. Stanley. Douthitt had just turned 21.

An attorney appointed by the court filed a formal application for Douthitt’s death sentence to be commuted to a life sentence. But the attorney withdrew from the case, “regretting his legal ability had not been successful in saving the youth from death, but feeling he had done all he could.”

So Douthitt went back to his death cell, where all he had was his Bible, which had a small photograph of his mother wearing a Red Cross uniform pasted into the frontispiece. And he prayed: “God, please end my torture.”

“Every time one of them died, it was worse than death for me.” - Charles Douthitt

He listened as the other prisoners were taken from their cells to the electrocution chamber, some hysterical, some praying and singing hymns. Douthitt would pray and sing with them. He heard the guards read the death warrants, then heard the prisoners scream as they met their fate. Their deaths haunted him. He could not sleep and could not get the screams out of his mind. And he knew that the only release from his suffering would be his own trip to the chair.

“Each time the door of the death room is opened, I thought it was for me and that my time had been set,” he said. “And when they started that motor, it sounded like murder to me. After a man had gone in and been killed, I couldn’t rest for days. I’ve heard their cries and heard the thud they make when the voltage strikes them. Some of them died game — the way I’ll die — and others were afraid. And I suffered with all of them.”

“Every man that passed by, I put myself in his place, and every time one of them died, it was worse than death for me. When they would bring the body out on a stretcher, I would think how I would look coming out that way. Sometimes in the middle of the night, I would wake up with a start and listen, fearing I would hear the voice of a guard saying, ‘Everything is ready, Charlie.’”

Douthitt asked the warden, John Chilton, to intervene. “They are considering your case,” Chilton told him. But they were not. It seemed that Douthitt’s death warrant, after being passed to Governor Stanley, had never been signed. Stanley had left office, and the case had not been brought to his successor’s attention. As one newspaper reported: “So time passed as Charles Douthitt, who wanted to die, lived.”

In January 1920, three years after the murder of Simms, the US Census recorded “Charley T Doutheitt” [sic], now aged 22, as an inmate at Eddyville. Deputy Warden John Baldree said Douthitt was a model prisoner. “Usually, the men are kept here but a short time before being electrocuted, and I don’t get to know them,” he said. “But Charlie has been with me so long, I feel an interest in him. He has been pleasant and obedient, and somehow I personally feel a little bad when I think about his going to the electric chair.”

Desperately lonely, Douthitt spoke through the cell walls with the other condemned men, until they were taken to their deaths. “They took away every pal that came to me, one by one,” said Douthitt. Eight men — Pat Kearney, Jim Lawler, Lewis Harris, James Howard, Melvin Collins, Lube Martin*, Charles Music, and Will Lockett — were executed while Douthitt was on Death Row. “I hated to see them all go, for they were kind to me, and they were men. I felt for all of them, except Will Lockett.”

Will Lockett (who was born Petrie Kimbrough) was a multiple murderer who had killed three women and a ten-year-old girl, Geneva Hardman, whose head he crushed with a rock. (Lockett was black, and when a white lynch mob attempted to storm the courthouse to get at him, the Kentucky National Guard opened fire, killing six and injuring 50.) “When I think of what he did,” said Douthitt, “his case was different, and I think he got what he deserved.”

But it was Lockett’s execution in March 1920 that gave Douthitt the chance to be heard. On the night before the execution, newspaper reporters were allowed onto death row to interview Lockett. Douthitt called out to them from the adjoining cell: “It’s worse than death here, fellows! Won’t you do something? Tell them to go ahead and send me to that room or take me away from this hole! Tell them, if they’re going to kill me, for God’s sake, to go ahead and end my torture!”

“It’s worse than death here, fellows! Won’t you do something?” - Charles Douthitt

“It’s hell down here, penned up like a chicken in a coop,” he told the reporters. “Nothing but thoughts of death. I was drunk when I did what they put me in here for. God knows I’ve paid for it already. I’d like to live, but not in here. Do you think a man could live in this Death Row, hearing eight men’s dying prayers, and not be cured? Why, if they let me out of prison, I could go out in the world and tell other fellows to let the booze alone and to walk the straight and narrow. It’s the only road, believe me.”

A Louisville reporter promised to take Douthitt’s case to the latest state governor, Edwin P. Morrow. A few days later, the reporter went to Morrow’s mansion. “It’s news to me,” Morrow said. “I remember the case, but presumed he had already been electrocuted.”

The previous governor, James Black, said the case had never been brought to his attention, and suggested that the clerk of the Court of Appeals might not have certified the warrant to Governor Stanley back in 1918.

Eddyville’s Warden Chilton said he had not investigated Douthitt’s case because he presumed the governor had it “under advisement”. He said Douthitt had never made a formal plea in writing to prison officials or the governor.

On 23 March 1920, Governor Morrow commuted Douthitt’s sentence to life imprisonment. Morrow said that Douthitt had “suffered death already in seeing eight others die.” More than 30 months after arriving, Douthitt was removed from Death Row. He was placed with the general population, but Warden Chilton said he couldn’t be put to work for a few days as he was “so weak from long confinement in a death cell”.

“Mother’s Plea for Son Saves Him,” said one newspaper headline. According to the report, Laura Douthitt had appealed to the three successive governors to commute her son’s sentence. “It is presumed that Governor Stanley, in compliance with his promise to the mother, held off sentence indefinitely and merely overlooked the matter up to the time he left the governor’s chair.”

In August 1921, Douthitt was in solitary confinement at Eddyville after apparently attempting to burn down the prison’s harness factory. Kentucky law stated that any prisoner who attempted to burn a prison building could face a death sentence.

But Douthitt was not sent back to Death Row. Will Lockett was the last man executed at Eddyville in 1920, and there was only one execution in both 1921 and 1922. But from 1923 there were multiple executions every year — including seven on one day in 1928. Records show 427 people have been executed in Kentucky since Jereboam O. Beauchamp was hanged in 1826.

While the story of Charles Douthitt might seem like a century-old curio, it is, unfortunately, anything but. The death penalty remains in force in Kentucky, although executions have been paused since 2010 due to “inadequate safeguards”. The consequence is that every condemned prisoner must play a waiting game, with many waiting far longer than Charles Douthitt. As of January 2024, 25 men and one woman are on Death Row in Kentucky. One prisoner, Karu Gene White, has been waiting for his execution for 44 years — surely a fate worse than death.◆

News

IP Picks, my website showcasing work suitable for TV, film, and podcast development projects, has been updated. It shows which of my works are currently under option or available. You can find it here: ippicks.com

“IP” is intellectual property, in this case original writing, which can be source material for entertainment development projects. “Under option” means a producer has obtained exclusive rights to set up the property for production. I wrote more about this in a previous newsletter, which you can find here.

The Singular Discoveries podcast is still available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube and other podcast apps. Back in January, I put out a special bonus episode featuring brand-new stories plus a behind-the-scenes look at the making of the podcast. That was originally available to supporters who purchased the ad-free binge and bonus package, and it’s now available as a standalone instant download.

More next month. Please share and subscribe. Thanks for reading.

*The story of Lube Martin, a black man who shot a white policeman, apparently in self-defence, is told in this YouTube video. An attempted lynching of Martin by “one thousand of the mountain whites” was prevented by Governor Stanley, as related in this magazine clipping.

Main sources: Kentucky Interior Journal, 10 August 1917; Richmond Daily Register, 24 March 1920; Kentucky Courier-Journal, 28 March 1920; Louisville Public Media, 24 January 2024.