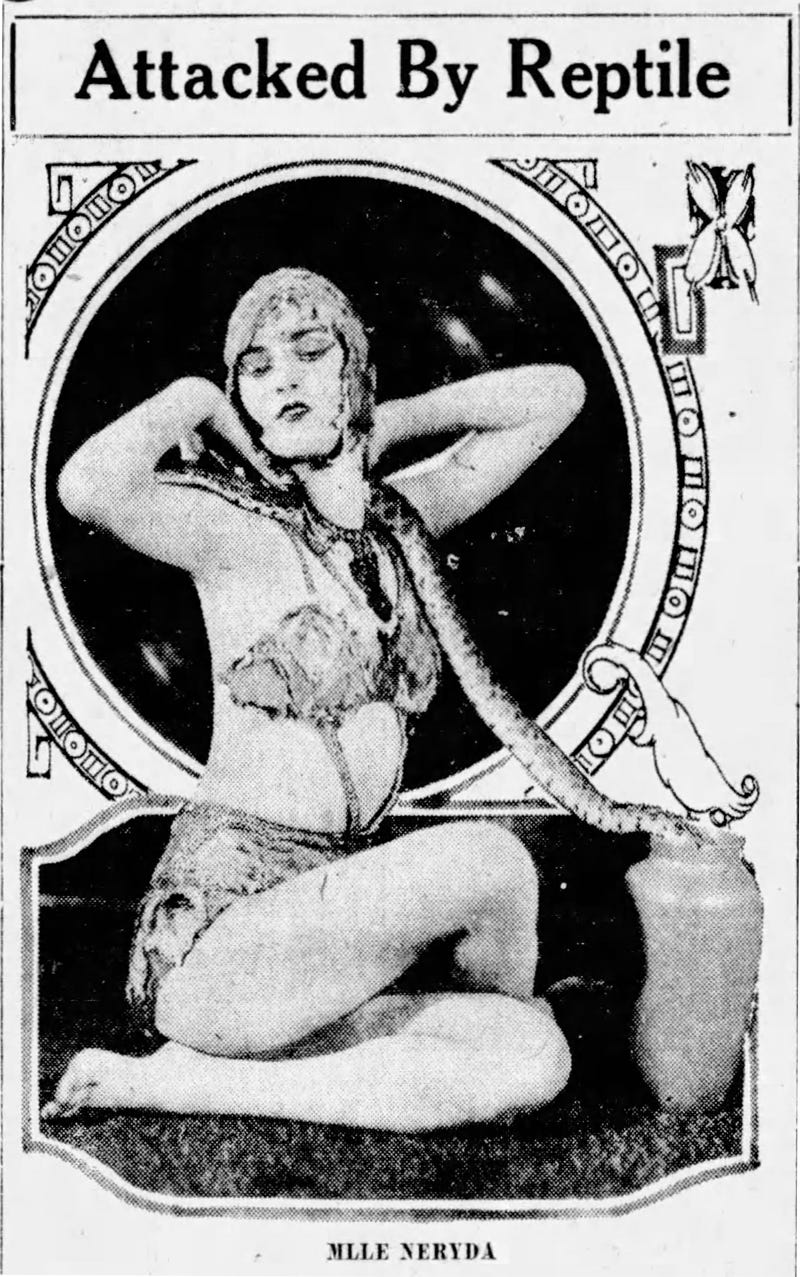

Attacked by Her Python; PLUS Ed Caesar

A snake dancer is almost killed by her pet, but is it all it seems? PLUS special guest Ed Caesar on The Moth And The Mountain

In April 1927, a snake dancer named Neryda was rehearsing for a show in Madison, Wisconsin, when she was attacked by her six-foot-long python. Neryda’s act involved luring the snake from a basket with a “strange, sinuous dance”. The Wisconsin State Journal, “A Fact-Finding Newspaper”, takes up the story:

Striking suddenly, unexpectedly, Allah, Indian python, nearly blinded its owner, Mlle. Neryda, during a rehearsal at the Parkway theater today.

“He didn’t mean to do it”, the dancer said fondly a few minutes later as she took the year-old snake in her arms.

Practising the steps of her act with the theater orchestra, Mlle. Neryda was just removing Allah from his basket and had turned her head away for a moment when the reptile struck her with a sound that could be heard all over the auditorium, and clipped his fangs into her eyelid, cutting the flesh in three places.

Joe Shoer, director of the orchestra, remembered boyhood stories and leaped to her side, sucking the blood from the wound. This undoubtedly soothed the pain, Mlle. Neryda said, but since the python is venomless, was not actually necessary.

Allah realized that he had done wrong, said his mistress, and immediately glided away beneath a pile of scenery, whence he was coaxed by the dancer. In the meantime, the musicians had descended from their perches on chairs, and summoned Dr. W. J. Ganser, who treated the wounds.

Despite Mlle. Neryda’s claims that Allah is “harmless,” she recalled an incident in Dubuque, Iowa, last year, when the python nearly strangled her.

There’s a lot to unpack here, not least Joe Shoer’s “not actually necessary” heroics and the fact that Neryda’s “harmless” python had previously nearly strangled her. We are indebted to the Des Moines Sunday Register Magazine for an account of that earlier incident from October 1926. Neryda had fallen asleep while reading a newspaper in her hotel room. “The beautiful danseuse Mlle. Neryda awoke gasping for breath to find her pet snake wrapped in six deadly coils about her throat,” the paper exclaimed. Neryda gave her recollection of what happened next:

“I have been handling snakes since I was a small girl, but that night was the first time in my career that I was ever frightened by one. Never before had I known the terror that paralyzed me when I was awakened by the pressure around my neck and realized that Allah was coiled around it, evidently bent on strangling me.

Lying there gasping for breath, I was amazed by the attack, for Allah loved me, if it is possible for a snake to know love, for I was her only friend and she had received nothing but kindness from me.

There was only one chance — I must find her head or tail and unwind her. A python cannot be removed by force. If one grabs the body and pulls, the snake will constrict the harder. Hurriedly but carefully I slid my hands round and round those coils. It seemed an eternity. When I made a mistake and grasped her body, she increased the pressure on my throat. Finally, I found her head, grasped it tightly, unwound her, and flung her across the room.”

Unbeknown to Neryda, her “desperate struggle for life” had woken other guests, who called the police. Captain Michael O’Connor and Detective George Stoltz arrived to find Neryda exhausted and unable to speak. Allah was lying motionless on the floor. Before O’Connor and Stoltz could take any action, Neryda picked up the snake, “caressed it, crooned like a mother over a child,” and put it carefully in its basket. “I was filled with fear that they would kill her before I could explain that she was my pet,” she explained.

“Human antipathy toward snakes is incomprehensible to Mlle. Neryda, who looks upon them as beautiful creatures, harmless if they are treated with respect,” said the Sunday Register. “Her experience with the python has not changed her attitude, and she believes the attack resulted from some fault of her own.”

As for the snake, Neryda said, “Allah thought it over for two days before she forgave me for treating her so roughly. The poor thing!”

According to her promoters, Neryda was born in Calcutta (Kolkata) in West Bengal to a French-English mother and a Syrian father. At the age of five, her maternal aunt — who disapproved of her sister’s relationship with a Syrian man — took Neryda to the United States and placed her in a convent in California. At 15, Neryda ran away from the convent and returned to Calcutta, where she got her love of reptiles from her naturalist father. She bore a scar on her wrist where her father had sliced open her flesh to increase the flow of blood after a rattlesnake bit her. Other sources said her father was a Hindu physician named Dr Ahmed Ajamy. Some sources titled her either Mary Neryda or Neryda Ajamy, but she insisted she had only one name — Neryda.

In fact, most of that backstory was fiction. Neryda was the stage name of Eva Newton, who was born in Ilinois in 1903. Newton performed as Neryda at venues across the country. She proudly handled rattlesnakes, cobras, pythons, and boa constrictors during her stage career. She first made headlines in 1926 after being fined for stopping traffic in Chicago when Allah got loose at a busy intersection. On another occasion, in New York, Neryda ran into baseball legend Babe Ruth. The Babe was intrigued by the snake and followed Neryda back to her room to watch it eat its dinner — a diversion that made him late for his duties at Yankee Stadium. Along with the reported snake attacks, this was all great publicity.

In 1928, Neryda was said to have charmed David Carnegie, the Olympic skeleton medalist and Earl of Northesk, who divorced his wife, but the romance did not last, if it ever really began. Neryda made headlines again in 1929 when she appeared in a Manhattan court with Allah the python around her neck. She was in court due to a dog rather than a snake. She was charged with allowing her blue chow, known as Wong, to run unmuzzled and was fined $2. By the time Neryda appeared at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933, as part of the Streets of Paris exhibit, Allah had been replaced by a new snake — Mu-Mu.

By the 1990s, Eva Newton was living in an Actors Fund retirement complex in New Jersey. She claimed to have owned more than 50 snakes during her lifetime. She had been forced to give away her last two when she moved into the complex and had only a plastic snake on her nightstand to remind her of her past. Eva “Neryda” Newton died in 1996 at the age of 93. She is buried in an Actors Fund plot at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York.

Here she is, pictured in the Shreveport Journal in 1990, “still limber” at 86:

Now let’s recommend some stuff, with special guest Ed Caesar:

Recommended:

The Moth and the Mountain by Ed Caesar

In 1933, the eccentric adventurer Maurice Wilson attempted to fly a Gipsy Moth biplane from England to Mount Everest and become the first man to climb to the summit of the world’s highest mountain. Unfortunately, he did not know how to fly a plane. Or climb a mountain. Things did not go well. Wilson’s amazing story was largely forgotten before the award-winning New Yorker writer Ed Caesar got his teeth into it. The Moth and the Mountain tells the story of a traumatised war hero driven to attempt the impossible by forces he does not seem to understand. It’s a surprising, evocative, romantic tale, and a gripping page-turner.

Ed Caesar was kind enough to answer a couple of questions:

Paul: What drew you to write about the very unusual adventurer Maurice Wilson?

Ed: It has taken me a decade to begin to understand why I was drawn so powerfully to Maurice Wilson. (Sometimes writers are compelled by subjects unaccountably, and sometimes there are clues in their past and their character.) What I can tell you is that I first read about Wilson in a brief description of his exploits in Into the Silence, by Wade Davis: a fine book about the early attempts to climb Everest. From that moment on, Wilson would not leave me alone. I sometimes woke up thinking about him. Why would a man with no climbing experience attempt to reach the summit of Everest, alone? Why would he fly a plane to the Himalayas? What purpose did his epic serve? These were the questions that roiled in my brain. As I said, it took me about ten years not only to answer those questions, but to begin to understand why those questions had gripped me in the first place. The short answer is: I was drawn to Wilson's pain, and how he expressed it so theatrically.

Paul: Can you recommend something like-minded readers might enjoy — something to read, watch, or listen to — and tell us why you enjoyed it?

Ed: My recommendation has nothing to do with my book, or any other book that's like it. I'd simply recommend that everyone watch the BBC series Once Upon A Time In Iraq. It is the most exquisite, harrowing, elucidating, and clearly narrated documentary. I can't recommend it highly enough. I don't think I've watched any TV documentary series that has affected me as profoundly. (And, for UK viewers, it's still on iPlayer.)

Many thanks to Ed. The Moth and the Mountain is out now in paperback. As Ed says, the full series of Once Upon A Time In Iraq is available on iPlayer in the UK. An abridged version is available on PBS in the US.

More next time, thanks for reading.

If you enjoyed this post, please share it with friends and followers via email, Twitter, Facebook etc by clicking this button. Thanks very much!

If you don’t already subscribe, please join us. Just click this button — it’s completely free and we’d love to have you onboard!

Main sources and images: Wisconsin State Journal, 25 April 1927, Des Moines Sunday Register Magazine, 31 October 1926, Shreveport Journal, 24 December 1990.