100ft Wave's Havoc

Transatlantic liner hit by biggest ever wave; PLUS big flood, Josephine Baker

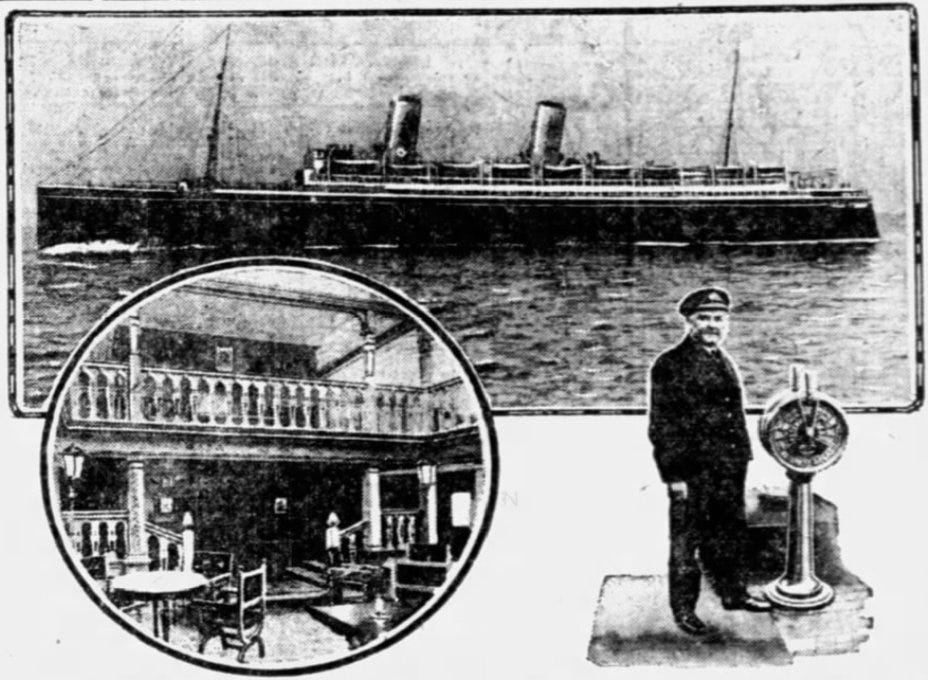

When the ocean liner Empress of France limped into New York some 36 hours late on its journey from Southampton at the beginning of February 1926, it brought with it a startling tale of transatlantic terror. Five days earlier, at 1.30 am on Sunday 31 January 1926, the Canadian Pacific ship had been struck head-on by a 100ft wave — perhaps the biggest wave ever recorded in the Atlantic.

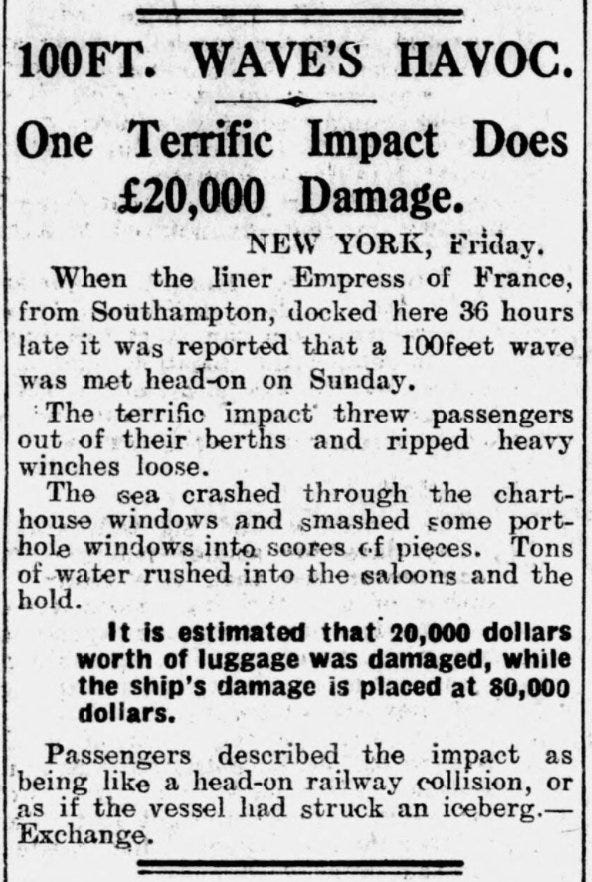

“The terrific impact threw passengers out of their berths and ripped heavy winches loose,” said one report. “The sea crashed through the chart-house windows and smashed some porthole windows into scores of pieces. Tons of water rushed into the saloons and the hold.”

Passengers described the impact as being "like a head-on railway collision or as if the vessel had struck an iceberg." The wave smashed through the ship's number 3 hatch allowing 50 tons of seawater to rush in, destroying all of the passengers' luggage. The Empress of France arrived in New York with its bulkheads dented and its 60ft booms “bent like hairpins”.

“Storm King’s Toy: Battered Like Matchbox by Monster Wave,” said the New York Daily News. Estimates said the incident caused $20,000 worth of damage to luggage and $80,000 worth of damage to the ship, totaling $100,000 — equivalent to more than $1.5m or £1.2m in 2022.

From the time she had left England, the crew reported, the France had not encountered winds of less than 45 miles per hour, and for most of the journey, the wind speed was 60 or 70 — at times reaching up to 90 miles per hour.

“I’ve been at sea for 35 years,” said the ship’s captain Edward Griffiths, “but this is the worst I’ve ever had. It was 17 kinds of hell.”

Despite the terrifying ordeal, with passengers and crew agreeing that it was the worst storm they had ever experienced, there was no panic reported onboard at any time.

The Empress of France was built in Glasgow in 1913. Originally launched as the Alsatian, the 18,500-ton, 570ft ship was briefly in service for the Allan Line before conversion into an armed cruiser during the First World War. At the end of the war, the Allan Line fleet was absorbed by Canadian Pacific, and the Alsatian was renamed Empress of France. In 1923, the France was one of the first ocean liners to circumnavigate the globe, sailing westbound on a round-the-world cruise, part of which was enjoyed by the Prince of Wales.

Its captain, Edward Griffiths, was a Welshman from the seaside town of Barmouth who began his seafaring career on a training ship at the age of 13. He was given his first command by Canadian Pacific in 1907. During the First World War, he commanded an armed liner that was tasked with transporting American troops to France. On 31 January 1917, Griffiths encountered a German U-boat, which fired seven torpedoes, narrowly missing his liner. Griffiths’ ship returned fire and hit the U-boat, which he reported disappeared from view, presumably sunk. The captain had several other brave encounters and by the end of the war had been promoted to commodore of the troop convoys.

Following the 1926 collision with the mighty wave, “an army of workmen” was immediately engaged to repair the France. It was scheduled to depart just six days later on a Mediterranean cruise. The ship did make that crossing with a full complement of passengers who were, according to one headline, “not afraid of waves”. It subsequently sailed on the Atlantic and then the Pacific before being retired and then scrapped on the Clyde in 1934.

Captain Griffiths had another terrifying experience, this time as commander of the Empress of Canada when it ran aground in dense fog on rocks near Albert Head on Vancouver Island in 1929. All 200 passengers were safely evacuated with their luggage, and the ship survived and was recovered. But when Griffiths made his final voyage before retirement in 1934, after more than 40 years of service, newspapers focused on the encounter onboard the Empress of France with the “worst storm of his career”.

Although Atlantic shipping continued to be plagued by occasional freak or rogue waves, the biggest were generally measured at around 60ft — substantially smaller than the one that hit the Empress. Wave height is defined as the distance from the trough of one wave to the crest of the next. It’s extremely difficult to gauge by sight in the pitch and roll of an angry sea — although experienced seamen are good witnesses.

Today, waves can be measured with some level of accuracy by ocean monitoring buoys. According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the world record for the highest wave ever recorded by a buoy is 62.3ft, measured at 6 am on 4 February 2013 midway between Scotland and Greenland in the North Atlantic. That’s taller than a six-storey building, and was generated after a “very strong cold front”.

In September 2019, during the approach of hurricane Dorian, ocean activity buoys off the east coast of Newfoundland detected several monster waves over 75ft in height —and one at 100ft. Those readings have not yet been verified by the WMO. (It took three years for the 2013 readings to be verified.) If so, they would prove that 100ft waves are possible in the Atlantic and confirm that the Empress of France had a very fortunate escape.

While seafarers dread to encounter such monster waves, some surfers actively seek them out. Big wave surfers dream of extreme waves and travel the world in the hope of finding them. 100 Foot Wave is an excellent 2021 HBO documentary (available in the UK on Sky and Now) following a group of surfers led by Garrett McNamara as they travel to Nazaré, Portugal. According to the Guinness Book of Records, the biggest wave ever surfed was rode by German Sebastian Steudtner at Nazare in October 2020. It measured 86ft.⬧

Next, from a big wave to a big flood:

Recommended:

Book: The Johnstown Flood by David McCullough (1968)

David McCullough was one of the great narrative history writers, and The Johnstown Flood is one of his best books. It’s a gripping, terrifying account of one of the most devastating disasters in American history. It happened in 1899, when the thriving town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, was swept away by a great flood following the collapse of a shoddily-built dam. More than 2,000 people were killed. McCullough painstakingly reconstructs the disaster using diaries, letters, and interviews with survivors to create a character-driven social history. McCullough died on 7 August at the age of 89.

Article: Josephine Baker Was the Star France Wanted—and the Spy It Needed by Lauren Michele Jackson (The New Yorker, 8 August 2022)

This is one of those book reviews that expands into a feature-length exploration of its subject, which the New Yorker does so well. The book is called Agent Josephine in the US (The Flame of Resistance in the UK), by British writer Damien Lewis. The subject is Josephine Baker, dancer, singer, nightclub entertainer — and spy for the French resistance during the Second World War. Jackson tells that remarkable tale and also explains how Baker went from a life of poverty in St Louis to becoming an international star of the Paris cabaret scene — attaining the celebrity she needed to camouflage her brave espionage. Read it here.

Oh hey, my book The Tyne Bridge is out on 3 November. You can pre-order here.

I’ll be talking about the book at the Books on Tyne Newcastle Book Festival on 22 Nov. Get free tickets here.

More next time. In the meantime, why not share this newsletter with your friends and encourage them to sign up? You know you want to.

Main sources: Daily Mirror 06/02/1926; Newcastle Chronicle 06/02/1926; Leader-Post (Canada) 06/02/1926; Daily News (New York) 06/02/1926; Times Colonist (Canada) 4/05/1925.

Enjoy the read? Reward the writer.

This newsletter is published ad-free, subscription-free, and outside of any paywall. We hope you enjoyed it. We believe writers deserve fair payment for quality content. We ask every reader to consider tipping the cost of a cup of coffee for this newsletter. All Ko-fi payments go directly to the writer. Thank you for your support. Click to tip.